Methodology

Employing critical theory, this study interrogates two normative assumptions posited by orthodox IR scholars-one epistemological and one ontological-that are directly linked to their inability to have predicted the EZLN uprising. First, it investigates the critical theorists’ position, as posited by Zeynep Gülşah Çapan (2017) and Cynthia Enloe (2004), that orthodox IR values only epistemologies in proximity to power, thereby neglecting the Indigenous epistemologies and knowledge systems significant to the EZLN communities prior to the uprising. Second, it delves into Enloe’s analysis of the foundational belief in orthodox IR that relationships between central and peripheral political actors are immutable and cannot be overturned (Enloe, 2004). Specifically, it focuses on orthodox IR’s prevailing notion that nation-states, perceived as ‘central’ actors in the international arena, maintain a fixed position of dominance, rendering all other ‘peripheral’ entities, such as Indigenous peoples, devoid of political agency and incapable of challenging this established relationship.

Furthermore, the study contextualizes how NAFTA’s implementation intensified the marginalization of Indigenous communities in Chiapas, Mexico, directly contributing to the EZLN uprising. The neoliberal policies embedded in NAFTA threatened Indigenous land rights and traditional ways of life, highlighting the disconnect between orthodox IR’s assumptions and the lived realities of peripheral actors. By examining these dynamics, the study demonstrates how critical theory can reveal and exploit the blindspots in orthodox IR to advance postcolonial endeavours.

Historical and Theoretical Context

International Relations (IR), emerging relatively recently with the advent of the Westphalian nation-state system (Zvobgo & Loken, 2020), stands as a nascent branch of political science (Hoffman, 1987). Scholars engage in discussions to delineate the exact scope of the discipline, specifically concerning the referent point of analysis that differentiates it from adjacent political disciplines. Orthodox conceptualizations of IR fixate on the entanglement of nation-states as the primary referent point, whereas critical theorists instead centralize “unconventional sources and unconventional ‘theorists’” (Zalewski, 1996, p. 347).

Indeed, orthodox conceptualizations of IR, corroborated by Martin Wight, posit that if political theory serves as the traditional foundation for contemplating the intranational nuances of a nation-state, then IR, by extension, can be considered to unitarily utilize the collective of nation-states as its referent object of analysis (Wight, 1960). However, the state-centric fixation of orthodox IR exists as a disciplinary blindspot, neglecting the political agency of non-state actors in the international arena (Buzan & Little, 2001). According to Enloe (2004), IR should centralize intranational affairs, specifically the political agency of ‘peripheral’, non-state actors, alongside its international considerations. This blindspot, stemming from orthodox IR’s inability to recognize Indigenous political agency, can paradoxically, if correctly exploited, further Indigenous emancipation by allowing Indigenous peoples to engage in surreptitious emancipatory endeavours hidden from the purview of orthodox IR, as evident in the EZLN uprising (Enloe, 2004).

Further theoretically contextualized, orthodox IR predominantly situates itself within what Robert Cox regards as problem-solving theories-those that envision political science, and by extension IR, as grounded in objective, ahistorical, and universal principles (Cox, 1981). Problem-solving theories strive to prescribe policies to remedy what their respective theorists believe to be objective political tenets. Conversely, critical theories endeavor to reveal the foundational ontological and epistemological assumptions that undergird problem-solving theories, exposing them to be rooted in normative assumptions, not universal truths (Cox, 1981; Zalewski, 1996). Notably, critical theories are not prescriptive but descriptive (Zalewski, 1996), existing as analytical tools to interrogate the theoretical blindspots, such as IR’s state-centrism, presupposing prescriptive, positivist, problem-solving theories.

Following this Coxian framework, critical theories can be further delineated by the methodologies in which they expose the normative assumptions presupposing problem-solving theories. For example, historical materialism seeks to expose the material assumptions undergirding a problem-solving theory’s positions (Krishna, 2021), while a more intersectional critical approach seeks to expose the ideologically structural assumptions undergirding such normative positions (Enloe, 2004). To reiterate within the context of IR, historical materialism, as a critical theory, might seek to expose the axiomatic tenets of liberal internationalism-a theory situated squarely within the confines of what constitutes a problem-solving theory-as materially contextual, serving the interests of capital. For example, whereas a liberal internationalist might regard the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) as teleological and a natural consequence of international cooperation among liberal democracies, a historical materialist might suggest that any proclivity among liberal democracies to establish international trade agreements (Walt, 1998), such as NAFTA, is only normatively assumed to be natural by liberal internationalists. They might argue that NAFTA’s encouragement for nation-states to encroach upon Indigenous land tenure (Enloe, 2004) is materially contextual, reflecting a means of accumulation by dispossession at the behest of capital, paralleling the ways in which prior modes of colonialism served the interests of capital via primitive accumulation (Krishna, 2021).

Additionally, the implementation of NAFTA had profound effects on Indigenous communities in Mexico, particularly in Chiapas, where the EZLN is based. NAFTA’s neoliberal policies threatened Indigenous land rights by promoting privatization and foreign investment in traditionally communal lands. This encroachment exacerbated existing inequalities and disregarded the socio-cultural significance of land to Indigenous peoples. The EZLN uprising in 1994 can thus be seen as a direct response to the neoliberal agenda embodied in NAFTA, highlighting the inadequacy of orthodox IR theories to account for the agency and resistance of peripheral actors affected by international economic policies.

Elucidating Orthodox IR’s Ontological and Epistemological Assumptions

Cynthia Enloe, utilizing both feminist and socialist frameworks (Enloe, 2004, p. 21), highlights the issue of state-centricity in orthodox International Relations (IR). Building upon her analysis, this article posits that this state-centricity presents an exploitable opportunity. Specifically, the focus on state actors within IR inadvertently paves a pathway toward Indigenous emancipation. This occurs as it grants Indigenous communities a form of political invisibility, shielding them from the constraints and impositions of traditional IR structures, thereby creating spaces for their agency and autonomy to flourish. This is manifested in the inability of orthodox IR scholars to foresee the Indigenous EZLN uprising-a failure stemming from the lack of a theoretical framework equipped to conceptualize the political agency of non-state actors. Utilizing critical theory, Enloe and adjacent critical theorists propose that the predominant focus of orthodox IR, especially the realist emphasis on state-centrism, is not objective but based on a normatively assumed realist ontology (Enloe, 2004). When this blindspot within orthodox IR is aptly leveraged, as seen in the case of the EZLN uprising, this perspective can paradoxically promote Indigenous emancipation. Indeed, whereas realist internationalism assumes nation-states act homogeneously and in their rational self-interest (Walt, 1998), the implementation of NAFTA triggered a sectarian fracturing of the Mexican nation-state, which challenges the realist fixation on the universality of the Westphalian nation-state (Enloe, 2004).

Moreover, beyond highlighting the universality and nation-state centricity of realist IR as being grounded in normative assumptions, Enloe-by employing critical theory-sheds light on two other normative presuppositions crucial to the realist international paradigm. The first normative assumption that Enloe contests, more thoroughly explored by Zeynep Gülşah Çapan, pertains to epistemology. Çapan asserts that orthodox IR, which encapsulates both realism and liberal internationalism (Walt, 1998), deludes itself into unitarily valuing non-peripheral epistemologies, mistakenly believing that only epistemologies within proximity to power are objective and worth studying (Çapan, 2017; Enloe, 2004). The second normative assumption pinpointed by Enloe, often neglected by orthodox IR, revolves around the presupposition that central-peripheral relationships are static and unchangeable (Enloe, 2004). This is founded on the belief that nationstates, viewed as the primary ‘central’ actors in the international arena, inherently relegate all other actors to a ‘peripheral’ status, stripping them of political agency and making this relationship seemingly immutable (Walt, 1998).

This article aims to utilize critical theory not only to corroborate Enloe’s critical observations concerning these ontological and epistemological assumptions within the context of the EZLN uprising but also to strengthen such claims by employing adjacent critical perspectives. The orthodox IR paradigm substantiates an epistemology that has institutionalized and naturalized colonial knowledge(s) (Krishna, 2021). Consequently, under this epistemic framework, ‘peripheral’ knowledges-including Indigenous knowledge(s)-are not recognized within their own ideological framework. Instead, they are perceived through their deviation, or lack thereof, from the standardized Eurocentric norm (Çapan, 2017). Due to this, within such Eurocentric epistemology, Eurocentric knowledge(s) are imbued with semantic associations of empiricism and objectivity, whereas Indigenous knowledge(s) are relegated to associations with ‘tradition’, ‘folklore’, and, if further dysphemized by Eurocentric hegemonic narratives, ‘uncivility’ and ‘barbarism’ (Çapan, 2017).

This hierarchical delineation of knowledge(s) exists, in part, as a consequence of dominant Eurocentric discourses neglecting to underscore peripheral historical narratives, guided instead by a metanarrative of ‘liberal democracy’ (Çapan, 2017). Orthodox IR imagines the development of the discipline as wholly teleological (Hollis & Smith, 1990), with a unitary progression towards Eurocentrism and away from the ‘barbary’ of peripheral epistemologies (Çapan, 2017). Liberal internationalism, which historically rationalized colonial endeavors as a means to ‘civilize’ Indigenous populations-thereby facilitating primitive accumulation and justifying ‘New World’ colonial endeavors-persists in endorsing contemporary neo-colonial agendas through analogous justifications (Zvobgo & Loken, 2020), manifest in contemporary ‘war on terror’ rhetoric of ‘spreading liberal democracy’.

Similarly, tangential strains of critical theory suggest that realism also implicitly operates under specific epistemic assumptions, placing a primacy on the nationstate as the paramount source of authoritative knowledge(s). Realist social-contract theory believes tacit compliance, or a social contract with a sovereign (the nationstate), to be paramount in maximizing a given nation’s security (Hollis & Smith, 1990). Furthermore, neorealism, a contemporary strain of realism (Walt, 1998), posits that on the international arena, all nation-states interact on an egalitarian playing field, echoing Hobbesian notions of equality and competition within an international anarchic state of nature (Walt, 1998). However, the existence of a global periphery demonstrates that such belief in international anarchy lacks nuance, and the existence of an epistemic intrastate periphery, such as the Indigenous peoples in Chiapas (Enloe, 2004), demonstrates that the nation-state should not be normatively assumed to exist as the paramount source of authoritative knowledge(s) to begin with.

Of course, the epistemological superiority of Eurocentric structures of knowledge reproduction and dissemination found in both realism and liberal internationalism are not self-evident; rather, as demonstrated by critical theorists, they are normatively assumed to “serve someone or some purpose” (Cox, 1981, p. 126). Although whoever “someone or some purpose” (Cox, 1981, p. 126) is, or whether it even constitutes a discernible political actor, is debated among critical theorists. Historical materialists, for example, believe ‘such purpose’ to be the process of capital accumulation (Krishna, 2021), while feminists may argue that ‘such purpose’ lies in the production and reproduction of hegemonic patriarchy (Enloe, 2004). However, in consolidating various strains of critical theory, it is elucidated that such epistemic ‘barring’ of what orthodox IR considers to be legitimate knowledge(s) remains axiomatically tied to social constructs of gender and race. For one, Enloe’s feminist framework suggests that Indigenous knowledge(s) in regard to the EZLN case study were regarded as peripheral, in part, due to the ‘othering’ effect presupposing the ideological emasculation and feminization of Indigenous populations within the masculine-centric field of orthodox IR (Enloe, 2004). Simultaneously, postcolonial critical frameworks elucidate that racial-focused theoretical delineations of IR have been relegated to their own anthropological subfields, distinct and epistemically alienated from the so-called ‘serious scholarship’ of orthodox Western IR (Zvobgo & Loken, 2020).

Furthermore, the implementation of NAFTA exemplifies how these epistemological and ontological assumptions manifest in practice. NAFTA’s neoliberal policies prioritized economic integration and free trade among the United States, Canada, and Mexico, without adequately considering the socio-economic realities of Indigenous communities in Mexico. The agreement facilitated foreign investment and privatization, which threatened communal land holdings and traditional livelihoods of Indigenous peoples in Chiapas. The EZLN uprising on January 1, 1994-the day NAFTA went into effect-was a direct response to these threats. The uprising challenged the state-centric and Eurocentric assumptions of orthodox IR by demonstrating the agency and political capacity of peripheral, non-state actors to resist and mobilize against global economic policies that adversely affect them. This underscores the need to re-evaluate the epistemological frameworks within IR that marginalize Indigenous perspectives and to recognize the fluidity of central-peripheral relationships.

By integrating the context of NAFTA and Zapatismo, it becomes evident that the EZLN’s mobilization was not merely a local phenomenon but a reaction to global neoliberal policies that orthodox IR theories failed to anticipate or adequately explain. This highlights the limitations of state-centric and Eurocentric paradigms in accounting for the complexities of global politics, especially the agency of marginalized groups.

A Paradoxical Silver Lining in Orthodox IR’s Theoretical Blindspots

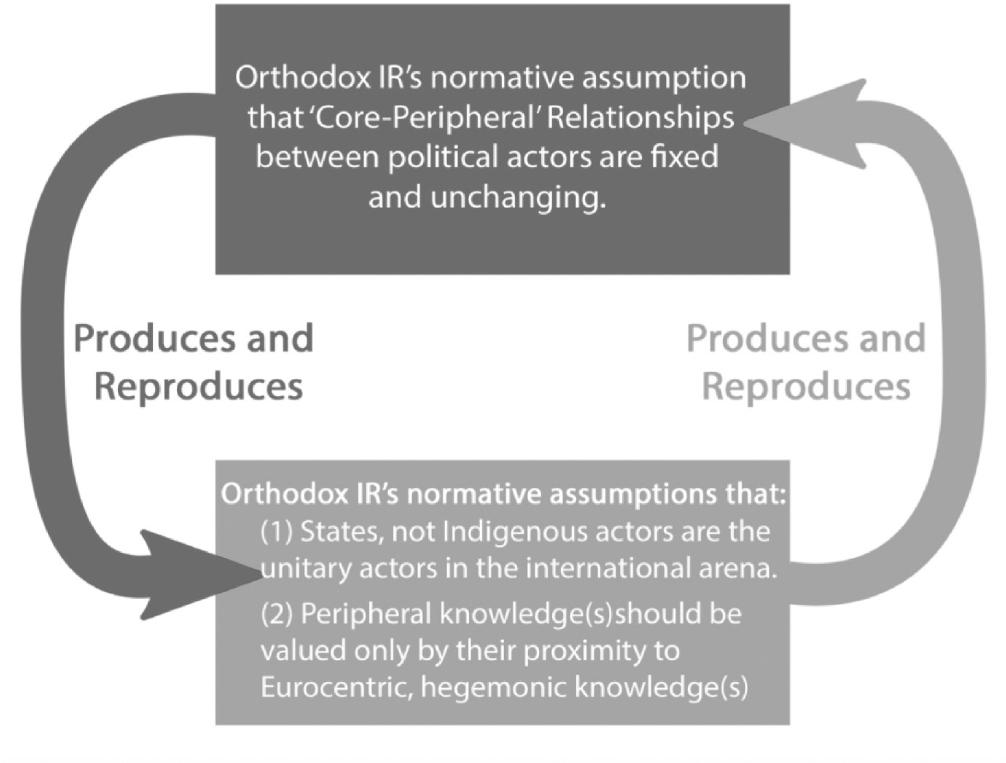

Perhaps the most dangerous ontological assumption made by orthodox IR, as brought up by Enloe (2004), in regards to maintaining its own preservation, is the belief that core-peripheral relationships between political actors are universally fixed. Enloe argues that orthodox IR neglects to care about how peripheral actors are “kept” far from power (2004, p. 23)-a crucial question if orthodox IR seeks to keep such peripheral actors from challenging its hegemony. This article addresses a tangential question: why does IR normatively believe that peripheral actors will remain kept far from power? Rephrased, why does it believe core-peripheral dynamics are fixed? In response, it suggests that such self-destructive assumption of orthodox IR, much like the Marxian base-superstructure dialectic (Harman, 1986), is itself produced and reproduced, and in turn, produces and reproduces other normative assumptions already explored. For example, both the ontological assumption that states are the primary actors in the international arena, and the epistemological assumption that peripheral knowledge(s) are of little value and pose no threat to existing epistemic international structures, presuppose the idea that peripheral actors, such as the EZLN, will always be relegated to the peripheral sphere. Simultaneously, the ontological assumption that core-peripheral relationships are fixed produces and maintains beliefs that peripheral epistemologies are of no value and that non-core, non-state actors should not be considered in crafting conceptualizations of IR (Fig 1.)

Reiterated, if orthodox IR sincerely subscribes to the notion of the epistemic inferiority of peripheral knowledge(s), it logically follows that such an ideological framework would perceive actors operating within these epistemic frameworks to maintain a peripheral status. Similarly, holding a genuine belief in the unilateral primacy of the nation-state as the foremost political entity on the global stage necessitates the view that nation-states ontologically retain a central role in international relations. Consequently, these underlying ontological beliefs perpetuate the normative presumption of a static relationship between core and peripheral entities, fostering a cycle of reiterated assumptions that these roles are fixed and immutable, with the same being true in reverse.

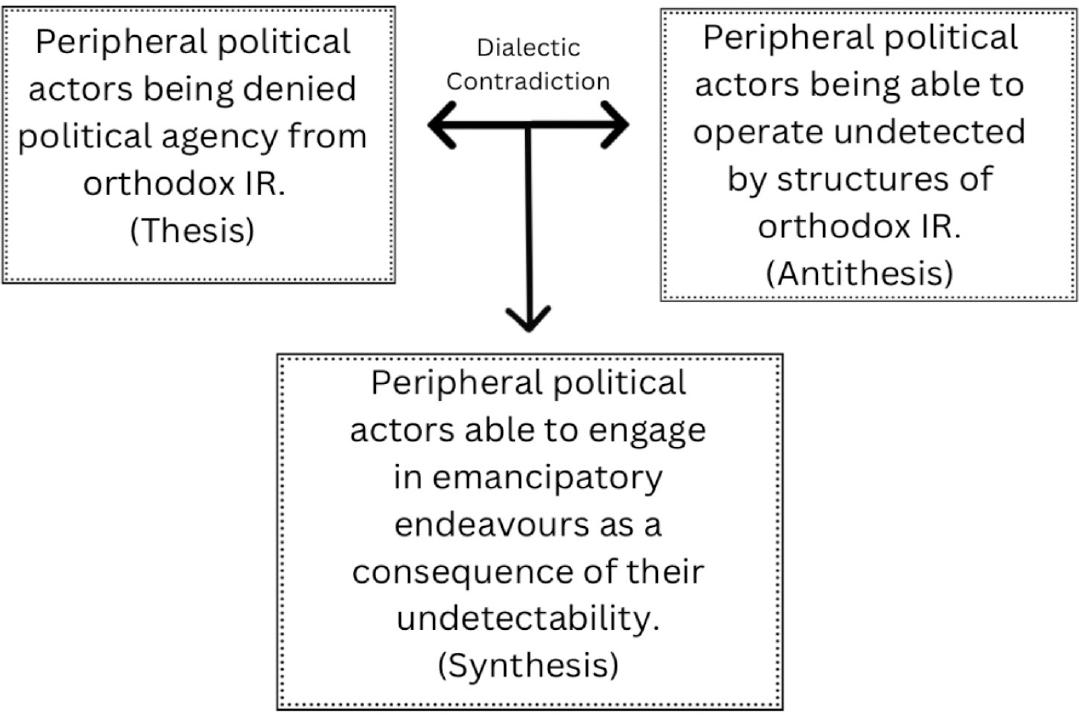

As such, the assumption that core-peripheral relationships are fixed remains exploitable, allowing peripheral actors to engage in emancipatory endeavours sheltered from the visibility of orthodox IR. To clarify, in propounding this exploitable blindspot within orthodox IR, this article does not advocate for realist or liberal internationalist accelerationism, as to do so would functionally only reproduce orthodox IR’s hegemonic paradigm. Indeed, a peripheral actor might, and should, advocate for their inclusion in international political discourse and the inclusion of their knowledge(s) in hegemonic epistemic spheres. Nonetheless, this alienation spearheaded by orthodox IR’s ontological and epistemological assumptions can paradoxically serve to emancipate political actors by allowing them to operate without being perceived as a threat by hegemonic institutions of orthodox IR. In a dialectical sense, the exclusion of peripheral political actors is a capitalizable contradiction that the EZLN successfully exploited and should be replicated, or at least serve to increase the morale of peripheral political actors engaging in parallel emancipatory struggles.

For instance, the EZLN’s ability to mobilize and resist without initial detection or serious consideration by the Mexican state or international actors illustrates how peripheral groups can utilize their political invisibility to organize and challenge hegemonic structures. The implementation of NAFTA, assumed by orthodox IR to be a policy affecting nation-states and their economies, overlooked the profound impact it would have on Indigenous communities. This oversight allowed the EZLN to build a movement that drew international attention to Indigenous rights and neoliberal exploitation, effectively using the blindspots of orthodox IR to their advantage.

Therefore, recognizing and exploiting these theoretical blindspots can be a strategic tool for peripheral actors. By operating beneath the radar of orthodox IR paradigms, they can develop grassroots movements and challenge the status quo, ultimately pushing for greater inclusion and recognition within the international system (Fig. 2).

Conclusion

Ultimately, utilizing critical theory, this article affirms the overarching contention that orthodox IR, typified by realism and liberal internationalism, is encumbered by limiting epistemological and ontological assumptions, which are laid bare in the post-NAFTA era context of the EZLN uprising.

In this critical epistemological investigation of orthodox IR, it explored the ways in which orthodox IR predominantly validates epistemologies not on their own terms, but rather by their proximity to hegemonic knowledge(s), thereby disregarding peripheral Indigenous epistemologies. This epistemological bias, combined with orthodox IR’s state-centrism, has been shown to produce and reproduce, and in turn, be produced and reproduced by orthodox IR’s belief that core-peripheral relationships between international political actors are fixed and unchanging.

Moreover, while not advocating for realist or liberal internationalist accelerationism, this article, corroborated by Enloe’s analysis of the EZLN case study, as well as the work of adjacent critical theorists, posits that orthodox IR’s inability to recognize the ontological and epistemological legitimacy of peripheral, Indigenous political actors leaves such orthodox approaches with a glaring, and perhaps exploitable, blindspot. Thus, peripheral actors might consider replicating the EZLN strategy of capitalizing on their political invisibility, or at least utilize such case study to bolster the morale of peripheral actors involved in concurrent emancipatory endeavours.

By acknowledging and exploiting the blindspots within orthodox IR, peripheral actors can challenge hegemonic structures and advocate for greater inclusion and recognition within the international system. The EZLN’s uprising demonstrates how Indigenous communities can mobilize against neoliberal policies that threaten their livelihoods and cultures, highlighting the need for IR theories to expand beyond state-centric and Eurocentric paradigms to account for the agency of all political actors.