1. Introduction and Background

With the intensifying digital transformation and changing practices in media content production and consumption, there is a growing need to identify new frameworks for responsible media governance.

Some inspiration for more informed policymaking toward a “responsible media environment” may be taken from earlier research studies and analyses that looked into media institutional makeovers as responses to the diffusion of neoliberal thinking and profit orientation, which have occurred since the last decades of the 20th century. As highlighted in those analyses, over the years, the increasing power of large media corporation owners has significantly contributed to the growing capital concentration and commercialisation in media productions (Jastramskis et al., 2017; Krūtaine & TetarenkoSupe, 2024). Likewise, with increasing platformization and fluctuations in traditional media businesses resulting from digital turnover, a need arises to explore which players in the current media ecosystems serve as dominant media agents and how their power restructurings occur in a changing digital ecosystem characterised by even greater takeovers and more intense transformations.

Media owners are generally described as influential agents whose motivation, competency, activities, and behaviour affect the risks and opportunities related to how media organisations fulfil or restrict the functions of news media for democracy (Harro-Loit, 2024). The most recent scholarship in the area of media ownership developments in some of the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries’ media, including Hungarian, Polish, Czech, and Slovak cases, characterises changes as “captures” that took place during the first decades of the 21st century after these countries’ media faced growing politically managed threats to their autonomy and independence (Mediadelcom, 2024; Štětka & Mihelj, 2024). These examples raise the question of whether, and to what extent, the public even knows who has the power to influence the way newsrooms operate and the content they publish and distribute. Put simply, the concept of “transparency of media ownership” (TMO) has become a crucial factor that needs to be considered prior to evaluating media production and its overall effectiveness.

This paper aims to expand on the concept of a “responsible media environment” by examining how transparent and accountable relationships with the audience are cultivated in markets characterised by particular structural aspects, including their limited size. As known, existing laws do not guarantee that their implementation ensures good media governance. Hence, it is necessary to focus on the assessment variables that effectively show the level of ownership transparency, allowing for a more comprehensive assessment of risks related to the existing or potential misuse of media ownership power (see, for example, results from the Euromedia Ownership Monitor [EurOMo]).

Our approach combines the perspective of media-owner transparency (regulations) with an analysis of accountability features through self-regulation. As we propose, this will enable us to evaluate whether the transparency of media owners’ self-regulation simply mirrors current regulatory conditions or provides opportunities to go beyond mere regulation and improve media accountability, namely seeking to establish closer relations with the public.

Our research will examine the structural factors influencing responsible media developments, as illustrated by examples from Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. This investigation will focus on (a) market size, (b) legal regulations concerning owners’ influence on editors’ appointments (editorial line), and (c) structural factors and market peculiarities that (d) impact the transparency and accountability of media owners.

2. Focussing on Small Markets: Characteristics of the Baltic Countries

Before delving deeper into transparency and accountability matters, we emphasise key traits defining media ownership changes in the Baltic countries.

Since the end of the Cold War in the 1990s, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania have undergone historically similar political, economic, and social transformations and have been similarly exposed to technological diffusion. At the same time, despite apparent similarities, some contextual differences are reflected in different dimensions of media transparency and media owners’ accountability. One quick example could be the recent acknowledgement of transparency in the Latvian and Estonian regulations for all business owners, which dates back to 2021. In this regard, the sole exception in Latvia pertains to joint stock company owners, who currently do not need to furnish information (Rožukalne & Ozoliņa, 2023); however, this is anticipated to change in 2024 (Latvijas Vēstnesis, 2023). In Lithuania, on the other hand, the annual requirement to report media business ownership changes has been established in the primary media law and has been active for decades (Law on Provision of Information to the Public; Įstatymas Nr. 0961010ISTA00I-1418, 1996).

As already known from prior analyses, several authors compiled a list of shortcomings seeking to reveal the peculiarities of CEE media systems, which, to a certain extent, also apply to the context of the Baltic countries. These include political influence on editorial independence, oligarchisation, and political parallelism; insufficient funding for public service media; and clientelism in relations with information sources (Bajomi-Lazar, 2015; Balčytienė, 2012, 2015; Örnebring, 2012). The list of features also includes an overtly formalised perception of journalism ethics and accountability (Bucholtz, 2019; Dimants, 2018, 2022).

Since the early 1990s, there have been changes in media ownership in the Baltic countries. The most notable changes are the two waves of privatisation: the early 1990s and during the global economic crisis of 2009-2010. In all three countries, the early 1990s brought an explosion in the development of media outlets. Nordic media giants, such as Schibsted, Marieberg, Kinnevik, Orkla, and Bonnier, entered the Baltic media markets during the 1990s but, for the most part, sold their shares back to domestic owners in the first decade of the 21st century during the economic recession or later in 2014-2017.

Moreover, similar to all small markets1, the media in the Baltic countries confront persistent risks linked to rising concentration (Jastramskis et al., 2017). Once more, the region’s unique characteristics are apparent: due to the size and wealth of the countries, the oligopolistic market structure seems inevitable in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

In oligopolistic media environments, market size refers to the reach and potential media audience influenced by the number of newsrooms or outlets offering journalistic content. In the third decade of the 21st century, the Baltic market is dominated by a few large media corporations of Estonian origin, Ekspress Grupp and Postimees Grupp, which control most of the media market in Estonia and, to varying degrees, also the media in the other two countries, namely Latvia and Lithuania. In addition to these two companies, All Media Baltic group, owned by the Lithuanian telecommunications company Bitė, is an influential player in Lithuania and the Latvian digital and audiovisual media market, where the share of national media ownership is decreasing.

Another exceptional feature of the Baltic media companies is that the media production functions of the largest commercial media companies are currently highly implicated with non-media businesses in all three countries. For example, when Margus Linnamäe became the leading owner of Postimees Grupp in 2015, his main business interests were related to pharmaceutical sales, medicine, and entertainment businesses. In Latvia, national media owners had been active in trade ports’ businesses, real estate, retail, entertainment, and so forth.

At the same time, accountability risks are less apparent in the Baltic states than in other CEE countries. For example, in Latvia, the media environment experienced the oligarchs’ takeover of Diena, the most significant media title in Latvia since 2008 (Rožukalne, 2013). These changes identify only one of many examples of the coexistence of modern, professional, and instrumental journalistic cultures (Dimants, 2022) in Latvia’s hybrid media system. Lithuania’s media landscape, the largest in population and advertising market among the three countries, is varied and wide-ranging, with online media regarded as traditional newsroom players. This situation is one of the reasons for the low online media fractionalisation (polarisation), which implies that radical narratives struggle to gain traction in the public arena (Horowitz & Balčytienė, 2023).

Another significant factor influencing the Baltic country’s media market and journalism culture is the historical and current location-based links with neighbouring Russia. This risk is caused by Russian Government-controlled media targeting the citizens of the Baltic countries with propaganda content. Distributed by powerful intermediaries (telecommunications companies), this content, for a long time, directly and indirectly affects the media structure available to the audiences in the Baltic countries. The influence of Russian state-run television channels was countered only after consistent public pressures were applied to major telecommunications companies following Russia’s largescale invasion of Ukraine. Before that debate, telecommunications companies were not seen as influential political media agents. It was also disclosed that some players depend on Russia’s financial influence among media owners in the Baltic states, but these connections lack transparency.

Considering these features, our paper focuses on small countries and their media systems, where the gaps between various hierarchical layers in society are minimal (“everyone knows each other”), and the major media owners are generally familiar figures - which means that there is a high level of “proximity” among stakeholders which increases “informality” (Balčytienė & Malling, 2019). Due to these particular structural conditions, a considerable enhancement in transparency and accountability regarding how owners influence editorial work is essential. The “proximity” and “informality” factors highlight the unique aspects of national media culture stemming from the interactions, pressures, and influences among different stakeholders in the media ecosystem (Balčytienė & Malling, 2019; Balčytienė & Morring, 2019; Örnebring, 2012).

3. Theoretical Framework

Our study adds to the idea of transparency in media ownership and control analyses by addressing the shortcomings of formal transparency, especially when considering ultimate decision-making power (Tomaz, 2024).

In our view, alongside the criterion of “who” is transparent (investigating media owners and actual beneficiaries), the possible implementation of transparency regarding “what” and “how” (focusing on the influence of owners on editorial independence and responsibility) is of greater importance. Acknowledging the complexity and contradiction of the notion of the media owners’ transparency and control, in our research, we analyse TMO by employing the actors’ and agents’ approaches (Archer, 2003). In our study, we define the characteristics of media markets and regulations to evaluate the influence of media owners and editors-in-chief in enforcing “media market accountability” (MMA), which is essentially their responsibility.

To understand and strive for responsible media, we must consider the regulations and self-regulation regarding ownership transparency within the broader media market size and structure framework. As shown in the following sections, we view the owners’ impact on selecting editors-in-chief as crucial in addressing the formalism of media ownership transparency and understanding how media owners might influence editorial choices, such as guaranteeing editorial independence. As such, MMA focuses on transforming observed risks into opportunities via accountability instruments and tools.

3.1. Transparency of Media Ownership

Essentially, media ownership research aligns with the political economy approach to media’s role in society, addressing the expressions of power. In such a way, media power analysis requires examining which ideologies are implicitly integrated into media systems and how media organisations serve the dominant interests. In such a way, by revealing the media’s control over dominant power relationships in society, it also examines the influence of media owners on the potential for democracy (Pickard, 2015; Stetka, 2012). Likewise, it also discusses how media owners’ control is manifested because media ownership structures determine the production, distribution, and access to media (Potter, 2021).

Therefore, media ownership research should focus on studies that link media ownership structures to media content and impact, as well as their governance (Pickard, 2015). National context features play a significant role here, as the owners’ influence on media content is determined by the historically formed political and economic culture of a given region (Hallin & Mancini, 2004; Stetka, 2012; Štětka & Mihelj, 2024; Voltmer et al., 2021) and the legal environment that defines what kind of information about media ownership should be accessible to the public.

With the ongoing impact of globalisation and digitalisation, emerging companies from diverse sectors are joining the media market, viewing media production as merely one aspect of their overall business activities. Consequently, national media outlets in numerous countries are increasingly being integrated into various international corporations (Craufurd Smith et al., 2021). This shift leads to traditional media companies being supplanted at the ownership level by private equity firms, whose ownership structures remain obscure and do not require disclosure (Euromedia Ownership Monitor, 2022). In CEE countries, international and national oligarchs have been exerting a covert influence on political and economic processes (Balčytienė et al., 2015; Štětka & Mihelj, 2024). As key stakeholders, they impact areas of information welfare, such as media diversity and pluralism (Brogi, 2020; Centre for Media Pluralism and Freedom, 2024), and shape public trust in the media.

In his analysis, Tales Tomaz (2024) identifies multiple reasons for the gradual shift from pluralism to transparency in policy discussions:

while the early debates focused on ownership restriction, the 2000s saw a new, more diversified wave of policy discussions on media pluralism. ( … ) More recently, media ownership transparency gained prominence in this debate. ( … ) The concept of transparency has played a growing role in normative discussions on good governance, closely related to accountability. (p. 449)

It’s worth considering why discussing transparency is essential when the aim is to improve market accountability. Transparency encompasses the demand for information, citizens’ ability to access it, and the actual production and distribution of that information, as noted by Ball (2009). In discussing media ownership, “transparency” prompts a vital question: is simply listing owners’ names in the public company register sufficient to be seen as “responsible media”?

When examining the practical implementation of transparency, results from the Media Pluralism Monitor (Centre for Media Pluralism and Freedom, 2024) show that most examined countries require public authorities (usually official enterprise registries) to provide information on owners and to achieve a minimum level of transparency. In contrast, many European Union countries assessed by Media Pluralism Monitor do not have TMO-related laws that require disclosure to regulators or the public (Centre for Media Pluralism and Freedom, 2024; Craufurd Smith et al., 2021). Analysing the TMO regulation in detail, the information available in different countries is divided into “soft transparency” (identification of the persons responsible for the media organisation’s activities) and “hard transparency” (the regulation includes sanctions for avoiding the provision of information). Essential quality criteria for media ownership transparency are the requirements to provide information on ultimate owners and regularly update information related to owners. However, little focus is added on the effects of such requirements on media outcome and quality.

Media power and control and its impact on editorial independence are central to our discussion about the Baltic countries. As already noted, an oligopolistic market situation is more or less inevitable in the three countries. In small markets, it is only possible to have a few competing players in one market or media market segment, as competition among many players would drive all players economically weak and would not guarantee diversity of content. Thus, the key question becomes: how can we enhance media owners’ accountability for their actions, particularly concerning editorial independence and journalists’ autonomy, and further conditions that guarantee high-quality news content?

In the context of this article, transparency means that relevant information is (actively) made available to the public so that it can be easily found and that decisions concerning the editorial board’s work are explained and discussed in media. As known, the media industry has long been safeguarded by “trade secrets”, and currently, the General Data Protection Regulation further complicates the requirement for transparency. Therefore, the degree of openness or transparency is always under the pressure of normative aspects (principles and values) in dominant public discourses and the attitudes and needs of different actors with different agencies.

Since “transparency” can be interpreted in various ways, this article defines it as the explicit disclosure of the relationships among media organisation owners and editors-inchief. This definition also aids in evaluating “accountability” in the media market, which will be addressed in the next section.

3.2. Media Market Accountability

Evaluating media accountability tools and mechanisms clarifies journalism’s quality and media organisations’ ability to foster long-term audience trust. As Kreutler et al. (2024) emphasise, successfully implemented accountability practices can protect the media’s editorial independence from political or economic interference.

According to the conceptualisation of Kreutler et al. (2024), the MMA framework refers to media companies whose operations are determined by the audience’s media use, as well as navigation through supply and demand processes in the media business. Media owners and top managers are core determinants of market accountability. At this level, the main instruments and tools are internal ombudsman initiatives created by the media editorial office, letters from the editors to the audience, and platforms for regular information about error corrections, which help build long-term relations with the audience and explain the essence of the editorial line.

Analysing media accountability practices is only complete if normative ideals are considered. Kreutler et al. (2024) emphasise the importance of the political dimension as it reveals aspects of non-statutory regulation and self-regulation models in different media systems and political cultures. The creation of accountability instruments in the tradition of Western democracy is developed to ensure the availability of information, journalistic quality, and pluralism. However, in countries where democratic traditions are not that long and stable, both within and outside the European Union, there are enough examples when regulatory bodies such as media councils, professional organisations, or ombudsman institutions are politically instrumentalised to limit media freedom and even support censorship (Štětka & Mihelj, 2024).

We assume that the operational goals and values of media organisations can influence the quality of performance across other levels of accountability. This aspect is crucial when anti-media discourse is growing at the political level, and the quality of journalism is determined by the audience’s attitude (Klimkiewicz, 2019). Media organisations can adhere to accountability regulations, develop self-regulation tools, and emphasise the role of self-regulatory councils or undermine them by ignoring the activity of media ethics councils or treating the principles defined in the regulatory framework as mere declarations. In today’s media environment, we cannot assume that all news media operate in a manner that can be defined as “social responsibility”. This is evidenced by the well-known tendencies of media system oligarchy in CEE countries (Štětka & Mihelj, 2024) and the actual development of pseudo-media or pseudo-journalism (Gerli et al., 2018), which affects public trust in professional media.

Our analysis will explore the market accountability of news media organisations by evaluating how they utilise internal accountability tools.

4. The Analytical Framework and Methodology Applied to the Baltic Context

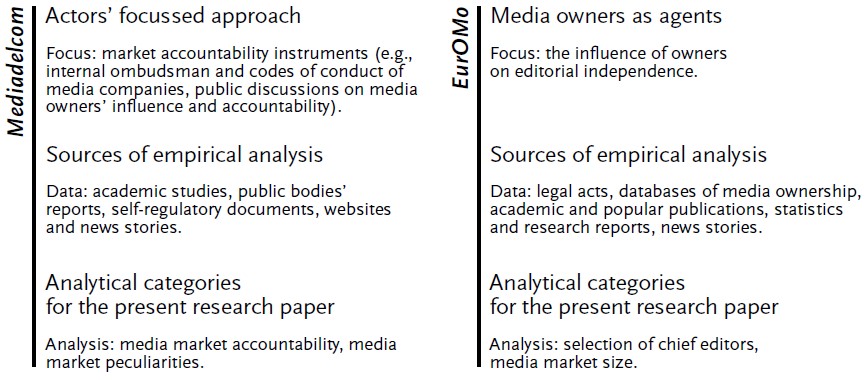

This paper combines key features of the conceptual frameworks of two recent initiatives: Mediadelcom and EurOMo. Both initiatives emphasise the essential standards required for ethical media practices that promote the growth of a “responsible media market”.

The Mediadelcom project’s methodology involves assessing media risks and opportunities using the “agent-actor approach” (Archer, 2003). This approach examines the media’s potential for fostering deliberative communication. Specifically, it investigates the role of media owners as active corporate agents whose responsibilities lie in upholding laws, establishing professional standards, and ensuring accountability. It could be said that the Mediadelcom project mixes the “processual” and “actor” approaches and highlights the importance of recognising diachronic changes and critical moments in the media market, such as ownership changes that directly affect media performance and, thus, accountability (Peruško et al., 2024). It points out the need to monitor media owners (as agents) whose motivations, values, roles, interactions, and competencies influence media performance. Meanwhile, the EuroOMo project methodology also centres on the transparency of media owners, highlighting their impact and interventions across various media markets. In this case, the transparency of media owners is assessed using six dimensions of media ownership and control, which include analysing ownership structure, management, economic control (economic power), relationships, distribution, and public policy (Euromedia Ownership Monitor, 2022).

In our analysis, we specifically selected four analytical categories and respective country data to expand the study of media accountability. We analysed secondary sources and retrieved findings from previous comparative research studies (Balčytienė et al., 2024; Jastramskis et al., 2017; Kõuts-Klemm et al., 2022), complementing them with publicly available current data (Euromedia Ownership Monitor, 2023; Mediadelcom, 2022) related to the three countries included in this study.

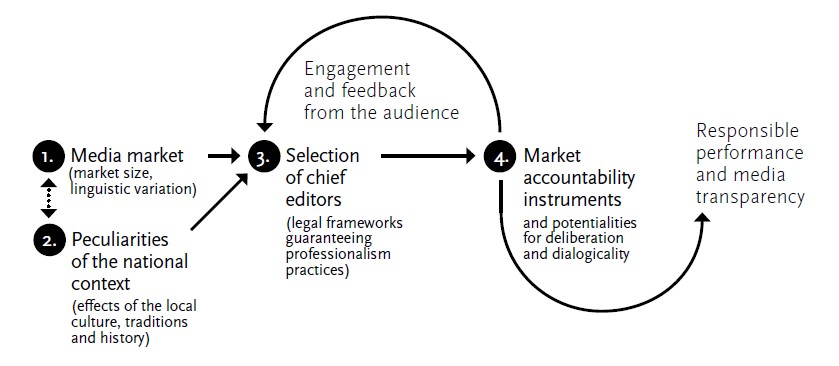

The four chosen categories in our model address the complexities of media operations at both systemic and organisational levels, allowing for an exploration of how media owners and managers perform their agency roles. The media market size data for the first of the four categories is sourced from publicly available statistics to compare small countries and support the assessment of the media market peculiarities, which we define as the second category in our framework. The third chosen category is at the heart of the EurOMo methodology and addresses the transparency of the selection process for the chief editor of news media. The evaluation of market accountability formats, discussed in Mediadelcom (Kreutler et al., 2024), is a fourth category that establishes connections between mezzo- and macro-level indicators. This category explores market accountability instruments, which may include media-internal ombudspersons, publicly available organisational codes of conduct, active public discussions about media ethics, as well as media-policy factors such as competition, concentration, and media ownership transparency. Briefly, the EurOMo indicator, which focuses on transparency in selecting media editors-in-chief, is crucial in evaluating the market accountability landscape in the three countries. Simultaneously, the Mediadelcom approach, which analyses market accountability formats, enables an examination of how news media organisations might invest in fostering deliberative communication. Specifically, it draws attention to instruments leading to accountability (Figure 1).

By analysing the three Baltic countries, we highlight the specificities of media ownership and identify connections between transparency in media ownership and the owners’ accountability. As revealed, in small countries, a crucial factor is the restricted media market, which is essential for preserving the identity of the nation-State. As noted in the above sections, the owners of a small media market cannot be well hidden by complex management layers. Still, as EurOMo’s monitoring shows, the critical issue is the lack of “relationship transparency” between owners and content producers (Euromedia Ownership Monitor, 2022). This aspect holds significant importance in the oligopolistic media landscape due to the limited availability of outlets and journalism jobs. Thus, in small countries, the owner’s impact on the editor-in-chief and the editorial board is more profound in shaping news output than in countries with numerous media organisations.

In our analysis, by selecting the four criteria, we emphasise the importance of developing standards for assessing how media ownership transparency can enhance media organisations’ accountability to their audiences. We suggest that improving media accountability and responsibility requires empowering professional agents with accountability tools. This includes promoting deliberative communication by increasing public “access to information” and “clarifying and justifying’ editorial decisions” (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 The essential standards required for ethical media practices to promote the growth of the responsible media market

In summary, the MMA approach and its instruments are vitally significant, especially in a small market. They facilitate public discussions on regulatory and self-regulatory tools and the journalistic culture that shapes relationships with owners. This approach also highlights the owners’ role in maintaining the quality and independence of news media.

4.1. Legal Context

According to the legislator’s view, in the three countries, the media sector is not seen as a distinct segment of business in relation to safeguarding public interests. In Latvia, between 2000 and 2017, the TMO regulation was part of the overall regulation of entrepreneurship (Latvijas Vēstnesis, 2000). The Commercial Law provided that information about its ownership must be disclosed to the registration authorities upon registering an enterprise. The media business is regulated as in all other economic areas in line with the dominant position statement, which is considered when the entity’s market share is at least 40% (35% for audiovisual media). In Estonia, electronic registers provide access to all media business ownership-related information; it is available to the public for free since 2022. Among other data, information from the insolvency register is publicly available, as well as annual reports, companies’ financial results, and annual reports of non-governmental organisations and foundations. According to the regulation, all entrepreneurs must declare the names of the beneficial owners of the companies they have established to the Commercial Register, and this data is also publicly available. In some cases, registers’ information is not accurate, as the beneficial owner data is not regularly monitored and updated by State institutions. There is a similar regulation in Latvia. Since 2021, free access to actual media owners’ data stored in the Enterprise Register has been available to the public for free.

Since 2011, the Commercial Law provision has been included in the Law on the Press and Other Mass Media in Latvia. In 2017, while improving the Law on the Prevention of Money Laundering and Terrorism and Proliferation Financing, it was supplemented with the obligation to determine the beneficial owner and a responsibility to report it to the Enterprise Register of Latvia (Latvijas Vēstnesis, 2008). However, a significant exception, sometimes used by media owners as well, is that, according to the Latvian Commercial Law, joint stock companies need not declare their owners. This has created a situation where some media owners related to politically influential persons and/or oligarchs were unknown for a long time.

In Estonia, the main risks to ownership transparency are related to the distribution and ownership of some radio outlets. For example, AS Taevaraadio, the license holder of Sky Media, employs one person and declares a comparatively low turnover (€27,000 in 2021). In fact, Sky Media, whose name is not listed in the Estonian Commercial Register (the English version of the broadcasting organisation’s name), has been operating in the radio business since 1995. In total, Taevaraadio manages six different radio stations, and the transparency of their management is limited. According to the information available on the skymedia.ee website, the company employs 24 people; eventually, some of the employees, such as programme hosts and those involved in advertising sales, are freelancers. There is no publicly available information on who defines editorial objectives and no information about the editors-in-chief’s selection processes.

Similar to Latvia and Estonia, Lithuania also has liberal media regulations. In Lithuania, the media business is regulated in the same way as in all other sectors of the economy, according to the assertion of a dominant position, which is considered if the company has a market share of at least 40%. There are no specific laws in Lithuania that would limit the concentration of ownership or market share of media organisations. As of 2023, a new system, Virsis, started operating. It is an integrated system of public information producers designed to provide data on information producers and providers registered in the Republic of Lithuania. It includes data on their management, type of activities, responsible editors, licenses, and income received (from political advertising, funds, natural persons, etc.). As outlined in media policy, the purpose of established regulation is to increase the publicity, transparency, and accountability of the activities of producers and disseminators of public information, ensuring that the public and competent State institutions can access and analyse data on media producers, disseminators, and their activities as specified by law (Įstatymas Nr. 0961010ISTA00I-1418, 1996).

4.2. Transparency According to Four Indicators

Evaluating analytical factors related to opportunities and risks indicates that while small countries share common characteristics, some uniqueness emerges as well. This reflects the cultural attitudes concerning responsibility practices among media owners in their media systems.

Although the media market of the three Baltic states2 differs slightly from country to country, market size does not determine media transparency, leading us to believe that the development of TMOs is a matter of media culture. For example, in Latvia, the influence of oligarchs on the media structure has been more noticeable than in Estonia and Lithuania. Also, the size of a country only sometimes correlates linearly with the size of its media market. For instance, Estonia has a smaller audience, yet its media market is financially larger than, for example, the one in Latvia. Furthermore, leading media companies in Estonia have transcended regional boundaries, extending their influence into other Baltic countries: this is revealed by examples of Ekspress Grupp and Postimees Grupp.

The media are mainly nationally owned in the three countries examined, with only a few exceptions (Bonnier, All Media Baltic). Another exceptionality is a high level of ownership diversity and significant cross-sectoral and intersectoral concentration in business activities (including media, printing/publishing, real estate, telecommunications, pharmaceuticals, and financial investments) where each owner engages financially. Also, the links between media ownership and those who possess economic or political power could be more obvious, leading to political or business influence risks. This finding reveals evident shortages in the availability and public accessibility of information and data about media owners and ownership types.

In all three countries, regulatory and self-regulation documents do not indicate a requirement for transparency regarding ownership impact on the selections of chief editors and their editorial independence. Furthermore, no examples of internal ombudspersons exist in any commercial media. Also, news editors usually do not explain their editorial decisions to the audience. These letters to explain editorial decisions to the audience are used in times of crisis or even more often for the marketing purposes of media companies.

The analysis of the media market’s peculiarities shows that each country has some TMO advantages. At the same time, some transparency limitations apply to specific media segments (radio market in Estonia) or media business participants (joint stock companies owners in Latvia). Inconsistencies in implementing transparency are also observed (Lithuania).

Also, professional media practices must incorporate more MMA formats (instruments and tools). MMA in Baltic countries is underdeveloped, except when journalists themselves apply pressure. Latvia needs more market accountability tools and a robust public dialogue regarding editorial independence. In Estonia, the public became aware of the influence of media owners on journalists’ independence during the two media scandals - one involving the owner’s appointment of the editor-in-chief of the daily Postimees and another concerning the “massive leave” of journalists. Both scandals also proved that the Estonian journalists’ professional community is sensitive to editorial pressure and somewhat accountable to the public. In Lithuania, there have been reported instances where private owners had opaque interests and connections, which became the focus of factchecking and investigations by journalists.

The analytical scheme, comprising four indicators, also highlights areas for improvement in media policymaking. One of the evident features, which we define as “informality”, reveals a dismissive attitude toward respect for rules and boundaries, apparent in all spheres, including elections of editors-in-chief or reporting on media ownership changes. As the case in Lithuania shows, the requirement to report on media ownership changes is listed in the law, and there are instruments to penalise those media groups/owners who ignore such an obligation; still, the law does not specify the period within which organisations must provide updated information on changes in ownership (Balčytienė & Jastramskis, 2022). Hence, partial compliance from the media authorities fails to foster an adequate accountability culture for media owners (and users).

In small countries, media owners typically gain recognition through informal transparency. However, we observed that their influence over editorial choices and the openness (transparency) surrounding the appointment of chief editors still need to be improved in these contexts. Small media organisations whose founders are journalists and editors have more significant power and influence, demonstrating responsible, independent journalism and higher standards of transparency (Lithuania, Latvia). In Latvia, international media proprietors provide greater transparency and accountability than national media owners. Whereas in Lithuania, the business daily Verslo žinios (Bonnier) was not as transparent about its ownership as expected from an international owner that claims to follow high editorial standards for accountability and transparency.

The examples suggest that the strongest chances to create a market accountability mechanism are tied to a robust journalistic community. The Estonian case described above shows that, even though the public lacks access to Postimees’ editorial policy, journalists’ firm beliefs in their autonomy and ongoing public discussions indicate potential ways to keep this issue alive in public discourse.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

As previously noted, the owners of news media outlets and their motivations, activities, and impact on various institutions in the country are associated with multiple risks to democracy.

Among those issues are a decrease in press autonomy and the politicisation of the media; the concentration of information power in the hands of a few and hidden individuals; the deterioration of journalists’ working conditions and the consequent decline in the news quality; and the diminishing prospects for maintaining or establishing a culture of accountability in the media market.

The four main factors chosen as the basis for the analysis may vary in their decisive importance regarding whether and to what extent the media can perform the function of a deliberative communicator for democracy. However, which combination of the above four factors defines the risks and opportunities associated with media owners in the Baltic states? Is any of the above factors so vital that the risk could be turned into an opportunity and vice versa?

The first factor is the small size of the media market in the Baltic states. As mentioned earlier, the size (small market) is an “implicit factor”. In other words, it creates an opportunity for conditions of non-formal transparency. The oligopolistic media landscape allows for a level of ownership transparency that larger markets cannot achieve: although specific details may be lacking, the public may hold informal knowledge about media ownership.

The example of the Estonian newspaper Postimees, described above, illustrates that in a small market, one owner’s attempt to “take over” the newspaper is noticeable, and journalists also have the leverage to influence the owner by leaving their positions. Attempts to reduce autonomy generally surpass the news threshold, and the workforce cannot be replaced quickly. On the other hand, when journalistic accountability and market accountability remain in tension for extended periods, experienced journalists may become disillusioned and choose to transition to roles such as civil servants or positions in communications where the wages are higher, and the work can be less stressful. Therefore, the dependence of market accountability on a substantial journalistic workforce alone may be unsustainable in the long term. Thus, the advantages of the small market can become risks - if the number of accountable professional journalists falls below a critical threshold.

As indicated by the second aspect of our analytical framework, editorial selection transparency needs to be improved. This is a sign of a nonexistent culture of openness. It explains why there is a “soft transparency” regulation of MMA in Latvia and Estonia (no consequences are defined if media owners’ transparency is not ensured). Formally, MMA regulation in Lithuania demonstrates a “hard transparency” approach, but its implementation is not full-fledged. Hence, the appointment of editors requires more transparency because it is not governed by law or self-regulatory codes. Furthermore, there are no selfregulatory mechanisms to shield journalists from the influence of owners. The rapid transition from socialism to capitalism in the 1990s did not allow time to develop a culture that would support holding business organisations accountable through regulations (such as macro accounting instruments or specific laws).

The absence of market accountability tools in the Baltic states increases risks in the current market. The autonomy of editors and journalists and the necessary working conditions for producing high-quality content can vary significantly; in some cases, such as in Lithuania, this responsibility may be substantial, while in others, it may be nonexistent. In this sense, Latvia’s situation is unstable and vulnerable, as the possible influence of oligarchs can be observed. This indicates the hybrid nature of the media system, where instrumental and post-Soviet journalistic culture coexist with the professional culture (Dimants, 2018). In 2022, Anastasiya Udalova, the spouse of Estonian businessman Oļegs

Osinovskis, one of the wealthiest people in Estonia, became the owner of the daily digital newspaper nra.lv. Latvian television’s analytical program “De Facto” reported that the new owner tried to influence the editorial decisions of nra.lv. Udalova was also offered the chance to buy the debts of the media outlet Dienas Mediji, owner of the daily newspaper Diena (Leitāns, 2023), and according to Re:Baltica journalistic investigation, she is involved in the creation of a media network (Dragiļeva, 2024).

The third risk factor focuses on the awareness of lawmakers (Parliament) and voters regarding the potential influence media owners may exert on news flow. This suggests that the development of MMA depends on media policymakers, who have prioritised the implementation of formal indicators of media ownership transparency and accountability within the European Union policy framework.

The fourth risk affecting the development of MMA pertains to the economic factors within the media of small countries. If transparency standards in the media market are set by a few influential media companies that operate in the context of liberal regulation, there are fewer opportunities for external factors related to market conditions to alter this situation. Therefore, MMA depends on the development of regulation and self-regulation in the direction of much deeper media transparency, revealing not only the structure of ownership but also its influence on content and essential editorial decisions.

To conclude, liberal media regulation has not contributed to developing a responsible media environment and media culture in the Baltic countries. The critical question is whether the priority in media regulation lies with the business interests of media owners or with the needs of the public and audiences.

As the geopolitical situation and market factors create a risk that the role of professional journalists and editorial agents may diminish, the only solution is to develop a culture of transparency. In order to implement MMA in small media markets, specific regulations should be established requiring media owners to disclose the appointment of the editor-in-chief and provide guarantees for the chief editor’s autonomy, which reflects their accountability in serving the public interest. Ideally, we believe that the regulation should mandate the media owners to ensure not only transparency in the selection process of the chief editor but also to provide an opportunity for journalists to participate in the appointment process, such as through involvement in the voting procedure for the chief editor.

Finally, a few additional remarks can be made in conclusion about the positioning of the Baltic states in comparison to other countries in the CEE region. As small markets, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are less affected by oligarchisation than the four countries of the Visegrad Group. However, this form of “protection” does not automatically provide formal and self-regulatory instruments. Instead, transparency is determined not only by structural features - such as market size and audience numbers - but also by the emerging social conditions for interaction between different agents, namely the values of individuals.

texto em

texto em