Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer worldwide and is more expressive among middle-aged women and in underdeveloped and developing countries.1 Its screening has proven to have a major impact on prognosis since it provides detection at the early stages of the disease. 2

Nowadays, in countries with well-organized screening and low rates of cervical cancer, its incidence is increasing, which can be explained by several factors. One reason is that exposure to HPV has increased over time. 3 Other reasons relate to the fact that certain types of sexual orientation, cultural beliefs, and socioeconomic status seem to be responsible for the lack of screening, even in well-developed countries. 1,4 Therefore, the development of strategies to improve cervical cancer screening must be a priority. Regarding HPV vaccination, authors consider that it is unlikely to lead to an increased incidence of cervical cancer because of diminished screening, despite the sense of protection from the vaccine in vaccinated women. 5 However, the impact of risk reduction will reflect on the cost-effectiveness of screening, whether done by clinician or self-sampling.

HPV screening not only has shown to be more effective as compared to cytology alone, but it also provides the possibility to be self-collected. 6 In fact, this type of HPV screening can engage many women participating in screening programs, eliminating cultural barriers or the embarrassment that some women complain about. It will also reduce health costs and the professional’s workload, along with more acceptance and populational coverage. 7 This type of sample can also play an interesting role in some contexts of reduced access to health care and scarcity of human resources, such as the one experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which there was a significant delay in cervical cancer screening. 8

There are few studies evaluating the accuracy of self-sampling, leaving doubts about its effectiveness, especially when influenced by factors such as the type of HPV assays, self-sampling device, and means of conservation. Furthermore, there is little evidence regarding the acceptability of self-sampling by women. 9 The purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the accuracy (non-inferiority) of HPV detection in self-samples compared to those collected by a health professional and assess women’s acceptability regarding this alternative for cervical cancer screening.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. 9 It was registered in the PROSPERO database (Prospero 2021 CRD42021251996).

The Population, Intervention, Comparator, and Outcome (PICO) components used to define eligibility criteria for this article were: population, sexually active women eligible for cervical cancer screening according to international cancer screening guidelines. Studies including individuals with a prior history of cervical cancer were excluded. For intervention, Index test - Cervical/Vaginal screening with self-sampling for HPV DNA detection test - including all different instruments of collection, transportation devices, or analysis me-thods. Reference standard: Cervical/Vaginal screening collected by clinicians, of any specialty, for HPV DNA detection test. Excluding other types of screening me-thods that involve healthcare providers (e.g. VIA, colposcopy, or biopsy).

The main outcomes were measuring accuracy in HPV detection (rates) between clinician-collected samples and self-sampling and if the accuracy in HPV detection rates between clinician-collected samples and self-sampling was similar for all HPV strains, high-risk strains, and low-risk strains. For additional outcomes, we defined the measure of acceptability of self-sampling by women, defined as women’s capacity to perform and accept the test.

Search strategy

Articles published in the electronic databases MEDLINE, CENTRAL, and Scopus were searched, along with unpublished studies, ongoing clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform), conference abstracts of the International Papillomavirus Society, and key journals. A free search on the Google Scholar search engine was also carried out. This research was conducted on March 4, 2022, and performed without any restrictions on dates, language, publication type, or region.

The following query was used: (HPV [title/abstract] OR human papillomavirus [Title/Abstract] OR (cancer [Title/Abstract]) AND (cervic* [Title/Abstract]) OR alphapapillomavirus [MeSH Terms] OR papillomavirus infections [MeSH Terms] OR papillomavirus infection [MeSH Terms] OR uterine cervical neoplasms [MeSH Terms]) AND (vaginal sample* [Title/Abstract] OR screening test* [Title/Abstract] OR test* [Title/Abstract] OR early detection of cancer [MeSH Terms] OR papanicolaou smear [MeSH Terms] OR Human Papillomavirus DNA Tests [MeSH Terms]) AND (self-collect* [Title/Abstract] OR self-sample* [Title/Abstract] OR self [Title/Abstract]).

Eligibility criteria, articles selection and quality assessment

Initially, an eligibility screening of the studies was carried out based on their titles and abstracts and regarding our inclusion criteria. A second screening was performed based on the full text. Eligibility criteria included studies that compared both methods of screening (self and physician sampling) using only vaginal and cervical biological samples and studies that contained data on its accuracy. We excluded studies published in non-Roman characters, studies only comparing self-samples themselves or using other types of samples (tampons, urine, non-vaginal/cervical). Regarding acceptability, women would have to undergo both tests (self and clinician) and answer a questionnaire. This selection process was conducted independently by three different authors. Researchers were blinded to each other’s decisions. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or, when not possible, by a fourth researcher.

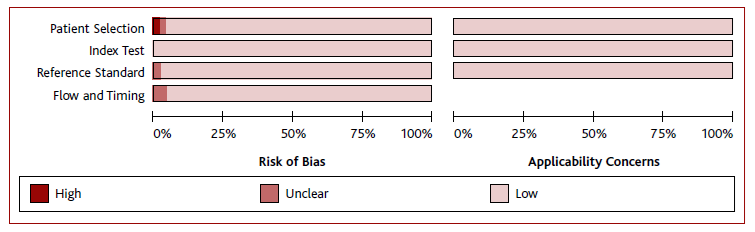

An assessment of the risk of bias was done using the Diagnostic Precision Study Quality Assessment Tool (QUADAS-2 tool). The four domains assessed were patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. Each domain was evaluated by the following classifications according to judgment - low risk, high risk, and unclear risk. Two reviewers performed the quality assessment independently. The assessment was performed using the Review Manager Software version 5.4 (RevMan, v. 5.4). For acceptability analysis, the risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB2) and for non-randomized studies, the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was used. Using the Rayyan platform, any disagreement was resolved by consensus or, when not possible to solve, by a third researcher.

Data extraction

Two authors, independently, extracted data using a data extraction form. Information was collected on general study details, HPV prevalence, tests’ characteristics, and diagnostic test results (true positive, TP; true negative, TN; false positive, FP; false negative, FN; sensitivity, SEN; specificity, SPE; and accuracy) or data that allowed their calculation, acceptability of self-sampling and preference of collection method, women follow up after screening and risk of bias information. Data was recorded using an Excel spreadsheet.

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was performed according to the technique and type of sample from each study, by subgroups. The pooled SEN and SPE of tests were estimated based on the TP, TN, FP, and FN rates extracted. SROC curves based on TP e FP rates were also built whenever possible. RevMan 5.4. and Meta-DiSc® 1.4.7. were used for data analysis.

As a high heterogeneity was expected due to the variation in sensitivity and threshold effect, a subgroup and sensitivity analysis was also performed. To assess acceptability a descriptive analysis was carried out with data based on responses given to questionnaires submitted after performing a self-sampling procedure. Heterogeneity tests were conducted (Q-test and I2 statistic), with inconsistency values I2 greater than 50% being considered as moderate heterogeneity and I2 greater than 75% defined as high heterogeneity. Outcomes with I2 values greater than 50% were submitted to sensitivity analysis and a random effects model was used.

Results

Selection of studies

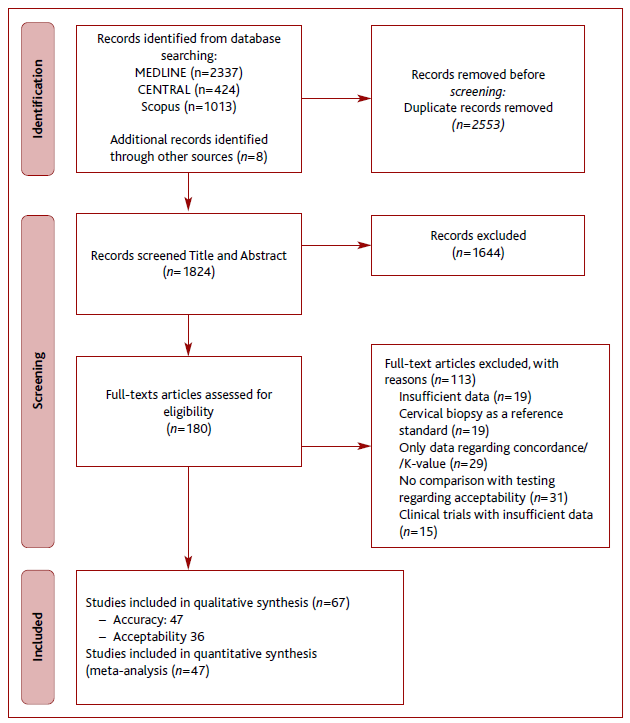

The literature search process is presented in Figure 1. A total of 2,553 articles were obtained. Following the removal of duplicates, reviews, meta-analysis, and systematic reviews, 1,644 articles did not meet our inclusion criteria, resulting in a total of 180 articles. One hundred and thirteen articles were excluded after full text analysis resulting in a total of 67 articles included, 47 regarding accuracy and 36 regarding acceptability. 11-77

Characteristics of included studies and participants

All 47 articles concerning accuracy were cross-sectional, with a total sample size of 18,615 women aged between 15 and 80 years and a total of 62 combinations between self and clinician samples. The study setting was divided into four large subgroups, considering some characteristics and prevalence of HPV: healthy women, concomitant HPV or HIV infection, known dysplasia, and medical history of cervical cancer. Concerning the healthy women subgroup, a total of 21 articles were drawn, including 12,876 women and an HPV prevalence ranging from 3.7-33.9%. For concomitant HPV or HIV infection, known dysplasia, and medical history of cervical cancer the numbers were six, 16, and two articles drawn, including 12,876, 1,875, 3,500, and 346 women and an HPV prevalence ranging from 21.7-84.3%, 30-78.4% and 78-89%, respectively.

HPV infection was assessed by tests targeting DNA except for APTIMA HPV assay, which targeted RNA. Regarding the material, in the self-sampling group, a swab was used in 23 studies, and a brush in 24. For physician-sampling, a swab was used in 10 studies and a brush in 37. Normally, cervical specimens were preserved in cytology-conserving media. Half of the studies reported that self-sampling tests were carried out at home and the other half in private medical offices, most of them with the help of written instructions. Both tests were made on the same day except for seven studies, with time intervals ranging from one and three weeks.

Regarding acceptability, only two studies were randomized control trials, with a total sample size of 17,706 women aged between 15 and 80 years old. The analysis was done considering three categories of acceptability: easy (20 articles - 6,459 women), convenient (13 articles - 6,192 women), and not embarrassing (15 articles - 6,647 women). The preference analysis included 25 articles (11,594 women) for self-sampling and 11 articles (7,341 women) for clinician sampling. Descriptive details and findings of the studies included in this review are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Assessment of risk of bias

Figure 2 displays the quality judgments for each QUADAS-2 item in all 47 included studies for accuracy, which quality appeared to be adequate. The quality judgment for acceptability using ROBINS-I also appeared to be adequate.

Diagnostic accuracy

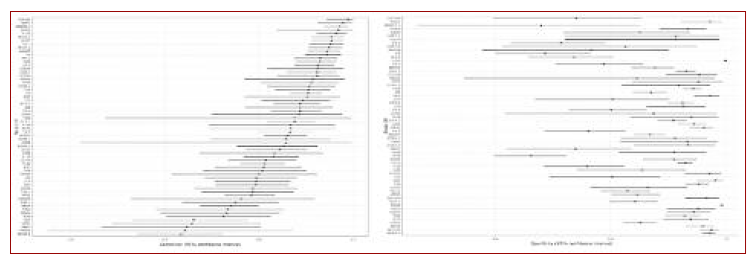

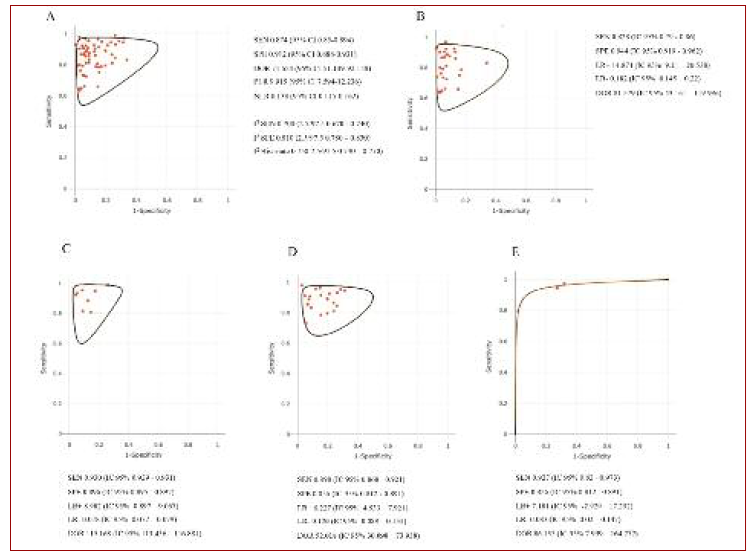

The overall SEN was 0.874 (95%CI, 0.85-0.894), overall SPE was 0.912 (95%CI, 0.888-0.931), diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) was 71.654 (95%CI, 51.149-92.158), positive likelihood ratio (PLR) was 9.915 (95%CI, 7.594-12.236) and negative likelihood ratio (NLR) was 0.138 (95%CI, 0.115-0.162). The SROC curve illustrates the relationship between SEN and SPE. I2 for SEN was 0.700 (percentile 2.5/97.5, 0.670-0.740), for SPE was 0.810 (percentile 2.5/97.5, 0.780-0.830) and I2 bivariate was 0.750 (percentile 2.5/97.5, 0.730-0.770), showing substantial heterogeneity among studies.

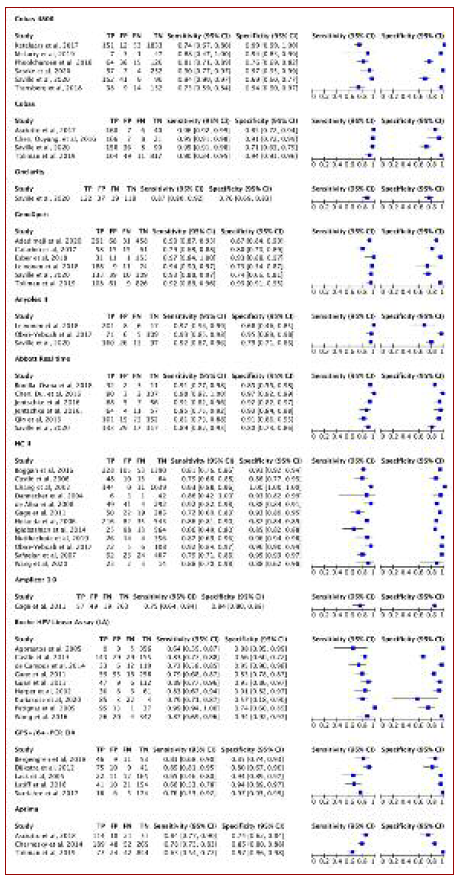

Subgroup analysis regarding the type of HPV test is shown in Figures 3, 3B and 4. Concerning the analysis of the four large subgroups, the results were: primary screening of generally healthy women SEN 0.828 (95%CI, 0.79-0.86), SPE 0.944 (95%CI, 0.919-0.962), PLR 14.874 (95%CI, 9.21-20.538), NLR 0.182 (95%CI, 0.145-0.22), and DOR 81.579 (95%CI, 43.161-119.996); known HPV or HIV infection SEN 0.930 (95%CI, 0.929-0.931), SPE 0.896 (95%CI 0.895-0.897), PLR 8.982 (95%CI, 8.897-9.067), NLR 0.078 (95%CI, 0.077-0.079), and DOR 115.168 (95%CI, 113.456-116.881); known dysplasia SEN 0.898 (95%CI, 0.868-0.921), SPE 0.856 (95%CI, 0.812-0.891, PLR 6.227 (95%CI, 4.533-7.921), NLR 0.120 (95%CI, 0.088-0.151), and DOR 52.018 (95%CI, 30.098-73.938) and established cervical cancer SEN 0.927 (95%CI, 0.82-0.973), SPE 0.856 (95%CI, 0.812-0.891), PLR 7.181 (95%CI, 2.929-17.292), NLR 0.083 (95%CI, 0.02-0.147), and DOR 86.135 (95%CI, 7.999-164.272). No difference was found between swab or brush, or between storage type.

Figure 3B Summary receiver operating characteristic plane. Notes: A = Forests plots and SROC plane obtained for all 62 combinations; B = SROC plane for primary screening of generally healthy women; C = SROC plane for known HPV or HIV infections; D = SCROC plane for known dysplasia; E = SROC plane for known cervical cancer. Label: SROC plane = Summary receiver operating characteristic plane; HPV = Human papilomavirus; HIV = Human immunodeficiency virus.

Sensitivity analysis

The overall sensitivity ranged from 0.875 (95%CI, 0.852-0.896) and 0.881 (95%CI, 0.859-0.9), and overall specificity ranged from 0.906 (95%CI, 0.884-0.925) and 0.915 (95%CI, 0.892-0.933). This outcome did not change by excluding any study.

Analysis of acceptability

The analysis was done regarding three categories of acceptability: easy, convenient, and not embarrassing. About 89.6%, 95.5%, and 89.3% of women considered HPV self-sampling easy, convenient, and not embarrassing, respectively. 62.8% preferred self-sampling and 55.6% clinician-sampling.

Discussion

This study showed that self-sampling, as a screening test, has high SEN (87.4%) and SPE (91.2%) to detect HPV and is not inferior when compared to clinician-collected samples. There was significant heterogeneity of results among studies. Looking closer at the impact of certain variables on the precision of self-sampling, the lack of methodological information made a more detailed analysis impossible. Nevertheless, our findings proved that the outcome was not significantly affected by women’s medical background (including previous HPV/HIV infection or lesions in previous cytology), type of sampling, material used, conditions of transportation and storage, or type of test used.

HPV screening for cervical cancer has been widely used in many European and other developed countries as a preferred screening method or as a complement to organized national screening programs. 78 It has shown to be highly cost-effective, as well as having high sensitivity to detect cervical cancer. 79 The introduction of HPV self-sampling as part of screening can help reduce costs and physician’s workload. 80 Moreover, it can have a major impact on increasing participation in cervical cancer screening. It has been shown that women who have never had this type of screening or who did not manage to meet a correct follow-up were twice as likely to participate if using the self-sample test. 81 Our study supports these findings, with a total of 62.8% of women choosing HPV self-sampling over the clinician one. Such outcomes can be explained by a variety of reasons. Not only does it ensure a safer environment, eliminating the discomfort described by some women during gynecological examinations, but it also allows more access to those who live far away from healthcare centers. Furthermore, it seems to be a simple and convenient way of screening, guaranteeing good acceptability among them. 55.6% of women favor collection by a health professional due to the lack of confidence in their ability to perform it. This demonstrates the need to invest in educational programs that reinforce the reliability of this method, otherwise, large-scale implementation will not be cost-effective.

Beyond acceptability itself, the rate of adhesion can be influenced by other factors. Although few studies are addressing these issues, age does not seem to be an influencing factor. Concerning the context in which these tests are carried out, there is discrepant data. Nonetheless, women in rural areas seem to participate less when compared to urban areas, which could be attributed to the lack of adequate logistics and resources. 82 If this proves to be the case, it is crucial to investigate further reasons for these discrepancies, since rural areas could benefit to a greater extent from the implementation of self-collection HPV tests.

This meta-analysis did not include studies that used samples obtained by urine or tampons since there is not enough evidence to validate their diagnostic accuracy.80 The quality of the instructions for the collection kits was not evaluated. Therefore, new studies must be carried out in this area to acknowledge if they are easily understood by women so that campaigns can be developed to promote self-sampling. Some authors have proved that sending the kit home has a higher participation rate than inviting women to sample with a professional.81 Other tactics, such as providing women with kits during their routine doctor appointments or making it possible to request online, may be an alternative to improve participation. 83

Regarding adverse effects or social harms, none have been identified specifically for self-sampling, since anxiety, distress, stigma, need for disclosure, and guilt for the cause after a positive HPV result commonly accompany an abnormal pap smear or clinical sampling for HPV, because of its sexually transmitted nature.84-85 Some of the disadvantages reported, were pain and physical discomfort, anxiety, insecurity concerning obtaining sufficient material for testing, and embarrassment in touching themselves. 79 Nonetheless, those events were not assessed in the studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Despite all the advantages mentioned above, HPV self-collection still does not allow the performance of reflex cytology, which implies notifying women to repeat the test with a professional when there is a positive result. 9 This fact not only increases associated costs but also reintroduces the discomfort that was supposed to be eliminated, questioning the applicability of this type of screening. 86 However, some promising studies suggest the use of DNA gene hypermethylation tests as an oncogenic marker, providing important additional information that will allow us to overcome this limitation in the medium term. 87 Additionally, in Next Generation Sequencing, a few human microRNAs and proteins are emerging as biomarkers that have shown promising results. 9,88

Since less than 10% of acute HPV infections progress to high-grade lesions or invasive cancer, overdiagnosis and overtreatment of transient infections are some of the main concerns for this type of screening. 89

Self-sampling may have limited impact in particular contexts, mostly in developing countries, given the associated costs and innovation technologies underlying the implementation of HPV detection strategies. Although the recent context of the COVID-19 pandemic enabled the development of a large number of infra-structures, the acquisition of advanced laboratory material and human resources all over the world, resources that could now be channeled to detect cervical cancer, due to HPV testing reagents, device and assay combinations, laboratory protocols and automated testing machines are the same used for testing COVID-19.8 Another advantage of self-sampling devices is that they do not need a cold chain and are stable after collection, this way allowing to minimize costs. 90

From our standpoint, HPV self-sampling is an important milestone in the history of cervicovaginal screening. Evidence emerging in the last few years has managed to support the idea that this method has the potential to improve adherence to screening and to promote earlier detection of HPV worldwide. Nevertheless, the assessment of the cost-effectiveness of moving from clinician-collected to self-collected HPV testing in cervical screening is complex and highly individualized. Numerous factors need consideration, such as the setting, vaccination coverage, and herd immunity, as well as the selected triage strategy.

This study reinforced this concept by conducting a simultaneous analysis of the effectiveness and acceptability of self-sampling methods and including a total of 18,615 women allowing conclusions to be drawn with confidence. However, there are no studies that properly assess the best implementation strategies, and cost-effectiveness and objectively define follow-up plans after a positive result, making further investigation necessary in this regard.

Conclusion

This systematic review with meta-analysis proved that self-sampling HPV screening is not inferior to clinician sampling and has good acceptability among women, making it a possible alternative or complement to conventional screening. This is a major step towards including more women in screening and ensuring earlier detection of HPV infections. The World Health Organization strongly recommended the use of self-sampling for the control of cervical cancer by 2030 and reduce cervical cancer by screening and treating identified cervical lesions. 91 Nevertheless, there is still low evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of this type of screening at a national level - some issues demanding attention as: how to and whom to offer self-sampling screening, triage, and follow-up of HPV positive cases and infrastructures and personal resources needed - should be investigated shortly, as well as investing in increasing awareness for cervical cancer and women’s acceptability about self-sampling by conducting studies that corroborate its reliability.

Authors contribution

Conceptualization, MPP, ISS, and VF; methodology, MPP; software, MPP; validation, MPP, and MA; formal analysis, MPP, and ISS; data curation, MPP, and MA; writing - original draft, MPP, MA, and FVB; writing - review & edi-ting, MPP, MA, LN, and ISS. All authors agree with the final version.