Introduction

This paper reflects general notes on a recently completed doctoral project1 designed to comprehensively study a group of Armenian illuminated manuscripts housed in the Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon. The codices studied were a Bible and three Gospel Books. These manuscripts were studied with an interdisciplinary approach for the first time, implementing methodologies from the History of Art, History and Technology of Artistic Production, and Conservation Science. The study provided insights into the political, cultural, and religious reality of seventeenth-century Armenian diasporic communities where the manuscripts were produced. It provided a perception of art and craftsmanship and shared practices within these communities. The art and materiality of the Armenian manuscripts of the Gulbenkian Museum reflect the practices of tradition and innovation, adopted by scribes and illuminators of the early modern Armenian scriptoria.

The Art Historical Approach

This study approaches the material within a holistic overview, where the visual, textual, and material characteristics are reflected. In the following section, this paper will present only the Art Historical discussion which reflects general iconographic observations of the Bible and Gospel illuminations2. Details on the manuscripts’ codicology can be found in the completed dissertation3,4. The materiality of the manuscripts was explored through molecular and elemental characterization mainly of the pigments, dyes, and inks. A closer look under the microscope revealed also very different painting techniques for each of the four manuscripts. These technical examinations indicated that the seventeenth-century Armenian manuscript production is faithful to its medieval traditions5.

Armenian Manuscripts in the Gulbenkian Museum

Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian was a prominent businessman, philanthropist, and art collector. During his life, he gathered an amazing collection of around 6000 art from all around the world. In his bequest, Gulbenkian specifically mentions his desire to have all his pieces of art under one roof, the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum in Lisbon which was inaugurated in 19696. Among carefully selected artworks such as statues, oil paintings, illuminated manuscripts, tapestries, tiles, and much more, four Armenian illuminated manuscripts are exhibited on the permanent display of the Gulbenkian Museum. These few but unique examples of Armenian art preserved in Portugal reflect the philosophy of the great collector - to find only the best pieces of art and antiques for his collection.

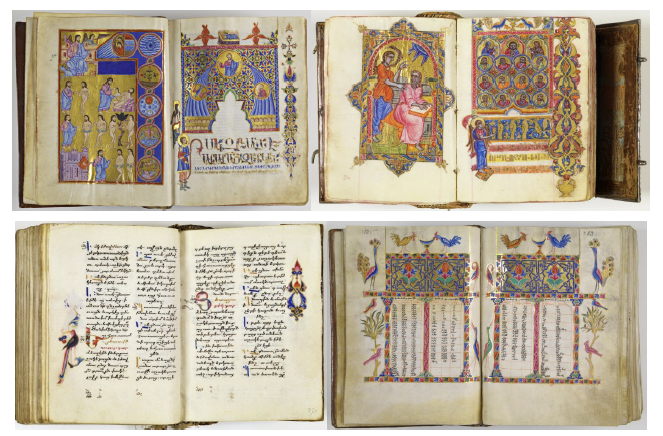

These illuminated manuscripts are a Bible (LA 152), and three Gospels (LA 193, LA 216, LA 253) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Four Armenian manuscripts of the Gulbenkian collection: a) MS LA 152, Bible, 1623, Constantinople, inks and pigments on parchment, 224x165 mm; b) MS LA 216, Gospel, 1686, Isfahan (New Julfa), inks and pigments on parchment, 108x079 mm; c) MS LA 253, Gospel, seventeenth century, Constantinople, inks and pigments on parchment, 154x114 mm; d) MS LA 193, Gospel, seventeenth century (1647-1693), Crimea, inks and pigments on parchment, 176 x 133 mm. © Museu Gulbenkian.

Gulbenkian acquired these manuscripts during his lifetime from intermediaries, art, and antique vendors or in auctions7. Fortunately, some preserved colophons of Gulbenkian manuscripts shed light on the origins of these unique objects. LA 152, LA 193, LA 216, and LA 253 were first described by renowned art historian Sirarpie Der Nersessian8. The colophons of these four manuscripts bring additional information to their historical background, introducing more details on scribes, artists, patrons, and production environments. The colophons are thoroughly discussed in the author’s completed dissertation9. Afterward, some of the manuscripts were reported in exhibition catalogs and scholarly articles10, being the Bible LA 152 receiving the most attention11. However, this group of codices may offer deeper insights to those interested in manuscript studies.

Historical Background

The Armenian manuscripts of the Gulbenkian collection were produced in the Armenian diaspora communities of Constantinople, Isfahan/New Julfa, and Crimea, during the seventeenth century. This period, strongly determined by the political situation of Armenia and the geographical shifts of its population, was a time of high development of Armenian art. It was a period of trade diasporas or communities, which played a crucial role in many aspects of Armenian life12. After having lost its glory as a medieval kingdom and being devastated by continuous invasions of Arabs, Seljuks, Mongols, and Turks, by the end of the sixteenth century, Armenian territories were constantly disputed and divided between the Ottoman and Safavid Empires13. Continuous conflicts and wars forced the local population to migrate, forming several diasporas in neighboring destinations, that progressively reorganized themselves into strong and self-sufficient communities.

During the seventeenth century, this phenomenon was especially apparent in some Armenian communities, fostered by the emergence of a new merchant class. This class of Armenian merchants became a key aspect in the economic and social developments of the early modern Armenian diaspora. But their impact was greater than imagined. These wealthy elites played an essential role in the promotion and patronage of Armenian art and architecture14. As a result, in the seventeenth century, Armenian artistic production reached its apogee in Constantinople, New Julfa, and Crimea.

Illuminations

Ornamental Program

The ornamental program in these four manuscripts is much familiar to the traditional Armenian style where the bird’s world, vegetal, geometric, personalized, and symbolic elements appear in marginalia, and elaborate initial letters, headbands, and incipit pages ornate the beginning of the text. The organized structure of text-image relation was carefully implemented by the scribes and illuminators. The distribution of these ornamental elements facilitates the reading of the text and is meant to visually guide the reader within the textual content.

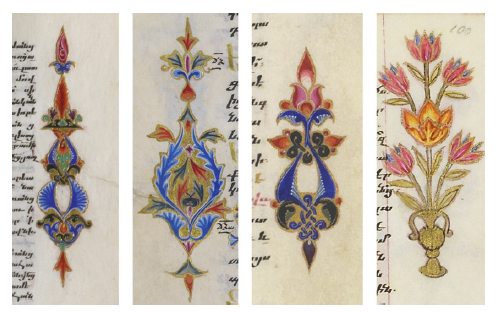

Both in the Bible and Gospels, the main books of the Old and New Testaments open with fully decorated title pages composed of lavishly ornated headpieces in the form of arcs (Fig.1). Ornated rectangular headbands indicate the main chapters within the books in the Bible. In general, each new passage in the Sacred Scriptures opens with an ornated initial letter, a zoomorphic or anthropomorphic majuscule, and is usually indicated with a marginal ornament. Plentiful marginal ornaments are mostly long-shaped compositions of palmettes and interlaced vegetal forms, except for Gospel LA 216, where these ornaments are merely flowers (Fig. 2). Sometimes small figures of biblical characters can be found in the marginalia, as in the case of Bible LA 152 and Gospel LA 253.

Fig. 2 Marginal ornaments in four manuscripts. From left to right: MS LA 152, Bible, p. 168; MS LA 193, Gospel, p. 112; MS LA 253, Gospel, fol. 55r; MS LA 216, Gospel, fol. 100r. © Museu Gulbenkian.

The Gospels (LA 193, LA 216, LA 253)

The pictorial program of the Gospels is reflected in the arrangement of illuminations, widely rendered in the Armenian manuscript tradition. At the beginning of each Gospel, there are fully illuminated folios of ten Canon Tables, including the Eusebian Letter (Fig. 1). All the Canons bear arched headpieces and are lavishly ornated with floral and animal patterns of vivid colors. Portraits of Eusebius and Carpianus are usually depicted in the first two Canons. The subsequent eight Canons are embellished with a variety of trees, vegetal ornaments, birds, and animals such as peacocks, roosters, partridges, lions, and monkeys. Each of these elements has a specific meaning and place in the context of Canon Tables, described already in several medieval texts by Armenian Church fathers and scholars of the time15.

Each Gospel Book opens with a portrait of an Evangelist and a fully illuminated incipit page, distributed in two separate folios facing each other. Matthew, Mark, and Luke are represented in inclined writing position, while John is standing and dictating the words to young Prokhoron. Incipit pages have elaborated headpieces, marginalia, and text written in ornate and majuscule bird-letters, with the symbol-letter of each Evangelist at the beginning. It was possible to determine some unique features of each of the Gospels.

Gospel LA 193

The Gospel LA 193 is entirely illuminated with frieze-like narrative miniatures telling Evangelical stories. These miniatures are composed of tiny forms and figures and merged in the text of almost every folio. This manuscript is familiar to seventeenth-century New Julfan scriptoria, known for its eclectic style combining Armenian, Persian and European elements. The LA 216 Gospel shows elaborated miniatures in very tiny scales. The forms and colors in these illuminations are imposing, and marginalia are catching the eye with floral compositions (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Flight into Egypt (detail). Left: MS LA 193, Gospel, seventeenth century (1647-1693), Crimea, p. 35. © Museu Gulbenkian. Right: Matenadaran MS 7651, Gospel, thirteenth century, Cilicia, fol. 26r. © Matenadaran Museum.

This Gospel is the exact copy of an earlier Armenian Gospel known as the “Gospel of eight artists” (Matenadaran MS 7651, 13-14th centuries), produced in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (1198-1375) (Fig. 3). The painter of this manuscript was working in the scriptorium of an Armenian monastery in Crimea. It is not known how he had access to the medieval model (MS 7651) that is now kept in Yerevan’s Matenadaran.

Before it arrived in the Matenadaran, the MS 7651 was probably displaced several times after the destruction of the scriptoria during the fall of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia in the 14th century. At some point in its displacement, the MS 7651 probably appeared in the attention of the 17th-century painter of the LA 193, which attests to his admiration for Cilician-Armenian art.

Gospel LA 216

The Gospel LA 216 is impressive for its elaborated miniatures in a manuscript of very tiny scales. This manuscript is familiar to seventeenth-century New Julfan scriptoria, known for its eclectic style combining Armenian, Persian, and European elements. The LA 216 Gospel shows elaborated miniatures in very tiny scales. The forms and colors in these illuminations are imposing, and marginalia are catching the eye with floral compositions (Fig. 4). Here too, the artist gets his inspiration from both traditional Cilician and New Julfan styles.

Fig. 4 Marginal ornaments in MS LA 216, Gospel, 1686, Isfahan (New Julfa), fols. 68r, 55r, 22v, 82r, 94v, 145r, 153r, 133r. © Museu Gulbenkian.

Gospel LA 253

The style of LA 253 Gospel is characteristic of a group of seventeenth-century Armenian Gospels produced between Constantinople and New Julfa. Unlike LA 193 and LA 216, the text itself has only marginal ornaments, but it begins with an iconographical cycle on Christ’s life traditionally found in Armenian illuminated Gospels16. This cycle precedes the Canon Tables and consists of full-page miniatures. In LA 253, it includes the Annunciation, Nativity, Presentation at the Temple, Baptism, Raising of Lazarus, Entry into Jerusalem, Washing the Feet, Juda’s Betrayal, Crucifixion, Descent from the Cross, Ascension, and Second Coming.

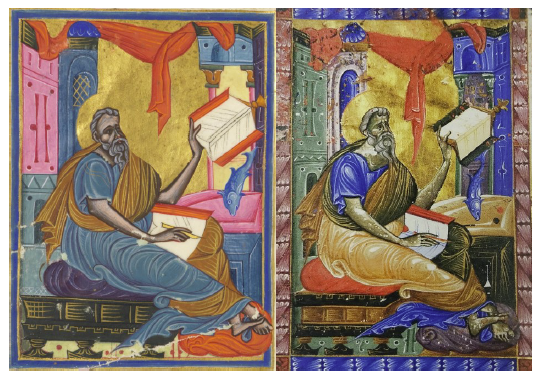

This Gospel also includes very classical Evangelist portraits, that resemble some in medieval Armenian Gospels, such as Matenadaran MS 2629 (1272-78, Gospel, Sis/Cilicia) (Fig. 5), Jerusalem MS 2568 (13th c., Cilicia), Beirut MS (1297, Cilicia), British MS Or. 5626 (1282, Cilicia), Matenadaran MS 6290 (1295, Cilicia), and Jerusalem MS 2563 (1272, Cilicia). As for the connection between LA 193 and Matenadaran 7651, the resemblance between LA 253 and medieval Armenian manuscripts attests to the revival and continuity of medieval artistic traditions, widely adopted by the early modern Armenian illuminators.

Fig. 5 Portrait of Evangelist Matthew. Left: MS LA 253, Gospel, seventeenth century, Constantinople, fol. 28v. © Museu Gulbenkian. Right: Matenadaran MS 2629, Gospel, thirteenth century, Cilicia, fol. 13v. © Matenadaran Museum.

The Bible (LA 152)

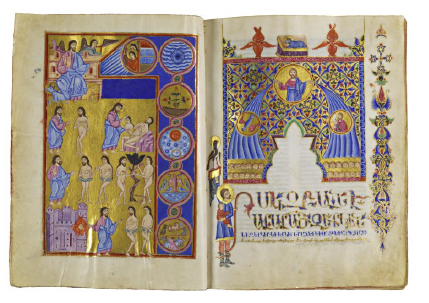

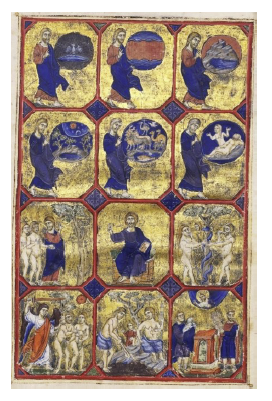

The Gulbenkian Bible LA 15217, opens on two fully illuminated pages that symbolize the first and the last books of the Old and New Testaments: The Book of Genesis and The Book of Revelation (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6 Illuminated page with scenes of Creation (left) and incipit page with scenes of Revelation (right). MS LA 152, Bible, 1623, Constantinople, pp. 13-14. © Museu Gulbenkian.

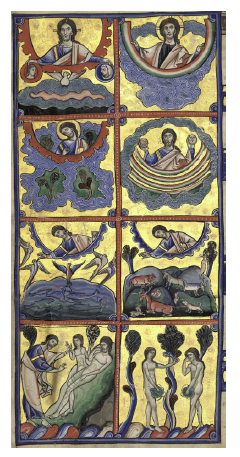

The Creation scenes are depicted on the full-page illumination (p. 13). The Pentocrator is figured at the top of the composition, enthroned, and surrounded by symbols of the four Evangelists. The three central horizontal registers represent the creation of Adam and Eve, Temptation, and the Expulsion from Paradise. Six medallions in the right margin are positioned vertically and represent the scenes of the hexameron. This composition is quite original since medallions were not common in Armenian Bibles until the 14th century. Then, examples of such “mise-en-page” can be found in Matenadaran MS 352, 14th c., fol.3v; MS 353, 14th c., fol.8r; MS 206, 14th c., fol.4r18, and afterward, this kind of geometrical structure seems to have been adopted during the seventeenth century, as it appears in several Bibles produced between Constantinople and New Julfa19.

However, it is still unclear which model has inspired LA 152. We assume that the influence is likely to come from the West through the circulation of medieval manuscripts as diplomatic gifts, because of mobility within trade routes and/or through religious missions toward the East20,21. Indeed, if rare in the Armenian illuminated Bible, Creation scenes in medallions can be found in several Latin manuscripts, very often within decorated initials (New York, PML, MS M.969, fol.5v; New York, PML, MS M.730, fols.9r-10r; New York, PML, MS M.66, fol.4v; New York, PML, MS M.953, fol.1r; Tournai, BM, MS 1, fol.6r; Porto, BPM, MS Sta Cruz 1, fol.2r, Dijon, BM, MS 562, fol.32r; Paris, B. Arsenal, MS 5211, fol.3v, Fig. 7). Other earlier examples such as Moutier-Grandval Bible (London, BL, MS Add. 10546, fol.5v), Pantheon Bible (Vatican, BAV, MS Lat. 12958, fol.4v), Bible of Pontigny (Paris, BnF, MS. Latin 8823, fol.1r), Bible of Souvigny (Moulins, BM, MS 1, fol.4v, Fig. 8) may be also considered.

Fig. 7 Illuminated page. Paris, B. Arsenal, MS 5211, Bible, 1250-1254, Acre, fol. 3v. © BnF - Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal.

Fig. 8 Illuminated initial. MS 1, Bible, twelve century, France, fol. 5v. © Bibliothèque Municipale de Moulins.

The page facing the Creation cycle in LA 152 is a fully illuminated title page of The Book of Genesis (p.14) with imagery of the Apocalypse. A lavishly ornated headpiece in the form of an arch occupies half of the title page. In this headpiece, Christ is portrayed in the central rosette, with a man on his left and a bird on his right side.

We interpret this image as a Christ-St. John-Holy Spirit composition. In the lower part of the headpiece, the twenty-four elders are represented. At the top of the headpiece is a lion-like lamb in adorned mounting, with seraphs on both sides.

In the lower-left corner of the page, a man is portrayed with a child in his lap and a book in the other raised hand, with a descending bird on it. The child holds a big serpent, curving around the feet of the man. This composition represents the initial letter "I" (Armenian "Ի"), to which an ornated text follows: "In the beginning…". We suggest that the man in this composition is Moses. In Armenian practice, it was common to portray Moses at the beginning of the Book of Genesis such as in the thirteenth-fourteenth-century Armenian Bibles (Jerusalem MS 1925, fol.9r, Matenadaran MS 345, fol.6r; Matenadaran MS 353, fol.7v; Matenadaran MS 206, fol.3v; Matenadaran MS 2627, fol.2v)22. As suggested by Der Nersessian23, this is symbolic: Moses receives not only the Ten Commandments from God but also the inspiration for writing the Pentateuch.

The above-discussed compositions are quite significant and make us think of inspiration models that the seventeenth-century Armenian artists had from local and non-local sources. Further comparative research may bring new insights into these unique illuminations.

Conclusion

The interdisciplinary study of the Armenian Bible (LA 152) and three Gospel Books (LA 193, LA 216, LA 253) preserved in the Gulbenkian collection in Lisbon demonstrates that each of these manuscripts is a unique testimony of Armenian art, produced in the seventeenth-century diaspora communities of Constantinople, Isfahan/New Julfa, and Crimea. The continued tradition of handwritten and illuminated codices in the given period indicates the societal demand and potential for the execution of such objects. The art of the four manuscripts reflects the tendencies appreciated in the scriptural practices of three communities of Constantinople, Isfahan/New Julfa, and Crimea, demonstrating the preference for medieval models by seventeenth-century Armenian artists. This is a clear indication of the continuity of local traditions in manuscript art during the period when new Western inspirations found their expression in many Armenian manuscripts, mostly Bibles. This dedication and faithfulness to local, predominantly medieval traditions were confirmed not only by iconography but also by material analysis of these Gulbenkian codices, confirming the use of color palettes of certain pigments that were copiously used in medieval Armenian illumination (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9 The representative molecular palette for the four manuscripts. Details from MS LA 193, Gospel, seventeenth century (1647-1693), Crimea, as well as one, the black, from MS LA 216, Gospel, 1686, Isfahan (New Julfa).

This research brings a novel approach to the field of Armenian manuscript studies, and Armenian cultural heritage in general. Such studies are essential for the unequivocal assessment of heritage objects and better strategies addressing their conservation and restoration.

Abbreviations for manuscript collections

Arsenal Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Paris

Beirut Arisdaghesian Collection (private), Beirut

British The British Library, London

Dijon Bibliothèque Municipale de Dijon, Dijon

Getty The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Isfahan All Savior Armenian Cathedral and Library, Isfahan

Jerusalem St. James of Jerusalem, Armenian Patriarchate Library, Jerusalem

Matenadaran The Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, Yerevan

Morgan The Pierpont Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Moulins Bibliothèque Municipale de Moulins, Moulins

Paris Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Porto Biblioteca Pública Municipal do Porto, Porto

Tournai Bibliothèque du Séminaire Episcopal, Tournai

Vatican Biblioteca Vaticana, Vatican

Venice The Mekhitarist Library of San Lazzaro Congregation, Venice

Bibliographical references

Sources

GULBENKIAN ARCHIVES (Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Arquivos Gulbenkian), Lisbon, doc. no. MCG 01470, MCG 02129, MCG 02085, consultated in October 2019.

GULBENKIAN ARCHIVES (Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Arquivos Gulbenkian), Lisbon, doc. no. MCG 04428, dossier of DER NERSESSIAN, Sirarpie, consulted in October 2019.