Introduction

Acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC) is a potentially life-threatening complication of ulcerative colitis (UC), which can occur at least once during the disease course in 25% of the patients. Moreover, ASUC can be the presenting feature in 10-20% of the patients with UC [1]. Mortality in ASUC has been decreasing in recent years due to the use of intravenous steroids and early colectomy for non-responders, but remains at approximately 1%, being as high as 4% for older patients [2]. Despite improvements in mortality, ASUC is still associated with significant morbidity and approximately 30% of the patients need colectomy and temporary or definitive ileostomy [3, 4]. Even though there was a 4%/year reduction in short-term colectomy rates after admission for ASUC, long-term and emergency colectomy rates remain unchanged [5]. Therefore, early identification, accurate risk stratification, and immediate, appropriate, and intensive management are needed to minimise morbidity, colectomy, and mortality.

Infliximab (IFX) and cyclosporine (CyA) represent the sole-approved drugs for rescue medical therapy in patients with ASUC when standard steroid treatment proves ineffective. Given its ease of use and the concerns with CyA short-term toxicity, IFX has become a common first-line salvage therapy in this setting in many countries. Nevertheless, IFX has the limitation of being associated with 20-30% primary non-response. Furthermore, given the recommendations to use anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF) as a first-line therapy in moderate-severe UC in many countries, such as Portugal, and the tendency for earlier use of advanced therapy in outpatients with moderate-severe UC, there is an increasing number of patients being admitted for ASUC, who have already failed or lost response to IFX [6]. Therefore, in an episode of steroid-refractory ASUC in this subset of patients, IFX ceases to be an appropriate rescue medical therapy and different salvage therapies to circumvent the need for colectomy may be needed. However, there is a paucity of data in the literature on how to approach these difficult to-treat group of patients. This narrative review intends to provide a comprehensive summary of the most recent data on this subject, particularly on the role of CyA in patients previously exposed to IFX, new maintenance therapies after CyA induction, and new emerging drugs for ASUC.

Standard Salvage Medical Therapy

ASUC is clinically defined by the Truelove and Witts criteria, and these patients have indication to start intravenous steroids [7]. Response is assessed after 3 days, as proposed by the Oxford criteria. Non-responders (≥8 stools/day or 3-8 stools/day and CRP >45 mg/L) face an 85% colectomy risk. If steroids fail, patients can either be submitted to colectomy or escalate to a second-line medical therapy, called salvage or rescue therapy.

CyA, a calcineurin inhibitor that selectively inhibits T-cell immunity, and IFX, a monoclonal antibody against the TNFα, are established salvage therapies for steroid-refractory patients with ASUC. CyA was the first therapy to be approved, with the original randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial published in 1994 and demonstrating an 82% improvement within 7 days on a dose of 4 mg/kg compared to a 0% response in the placebo group (p < 0.01) [8]. As CyA side effects seemed to be mainly dose-dependent, a further study demon-strated that a lower dose of CyA (2 mg/kg) had equivalent efficacy [9]. IFX was later approved for use in this context with a significantly lower rate of colectomy within 3 months of therapy when compared with placebo (OR 4.9, 95% CI 1.4-17, p = 0.017) and without significant side effects [10].

The CYSIF trial, conducted by the GETAID, was the first head-to-head, randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing the efficacy and safety of both CyA and IFX. The study included 115 patients, and none had previously been exposed to any of the drugs. CyA was administered initially through continuous intravenous infusion at 2 mg/kg/day and transitioned to oral formulation at 4 mg/kg/day in divided doses for 98 days, adjusted according to serum concentrations. IFX was administered with an initial 5 mg/kg infusion and additional infusions on days 14 and 42 for responders. Both groups started azathioprine after 1 week. The trial, designed as a superiority trial, revealed no significant differences (60% for CyA, 54% for IFX, absolute risk difference 6%, 95% CI -7 to 19, p = 0.52) on the primary outcome, which was a composite outcome for treatment failure (absence of clinical response or steroid-free remission during follow-up or an adverse event leading to treatment interruption, colectomy, or death). There was also no difference in colectomy-free survival at 3 months of follow-up [11].

Subsequent head-to-head trials, such as the CONSTRUCT trial, included 270 participants who could not have been exposed to either IFX or CyA in the 3 months before admission. IFX was given at a dose of 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6 and CyA at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day by continuous infusion for up to 7 days, followed by oral CyA at 5.5 mg/kg/day for 12 weeks. After this, therapy was at the discretion of the medical team. The primary outcome was quality-adjusted survival evaluated sequentially until 3 years of follow-up, and there were no differences between groups. There were also no differences in the in-hospital and overall colectomy rates [12].

Although these studies demonstrated no differences between CyA and IFX as salvage therapies for steroid-refractory ASUC patients, it is worth mentioning that in all these studies, IFX was used on a regular scheme and no dose optimization was carried. Severe bowel inflammation seems to be associated with increased faecal loss of IFX as was highlighted in the study by Brandse et al. [13] where it was demonstrated that patients that were clinical non-responders at week 2 had significantly higher faecal concentrations of IFX after the first day of treatment than patients that were clinical responders (p = 0.0047). Moreover, another study demonstrated that patients with a higher baseline C-reactive protein had significantly lower serum concentrations of the drug and that patients with low serum albumin and higher baseline faecal calprotectin levels also had a trend towards lower serum IFX concentrations [14]. This raised the possibility that an accelerated IFX regimen could be more effective than a standard induction regimen, although most studies to date have had negative results as was demonstrated by a systematic review where there were no differences in colectomy rates between both accelerated and standard IFX groups [15]. More recently, a retrospective study with a propensity score-matched cohort of steroid-refractory ASUC patients demonstrated that an accelerated induction regimen of IFX seems to be associated with lower short-term colectomy rates but not long-term colectomy rates [16]. The differences in these results can be partially explained by inadequate statistical power due to limited sample sizes and by a significant variability in clinical practice patterns in the management of hospitalized UC patients as was shown by a survey study among experienced IBD centres [17]. Results from the PREDICT-UC (NCT02770040) which is an open-label multi-centre RCT to assess whether an accelerated (5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 1 and 3) or intensified (10 mg/kg at weeks 0 and 1) IFX induction regimen is superior to standard induction in ASUC will help clarify this question.

Despite differences in induction regimens that need to be clarified to better compare the efficacy of both drugs, these studies have also demonstrated high rates of co-lectomy in the long term, low prevalence of sustained remission, and need to switch therapies, suggesting that it is also needed to better understand maintenance regimens which may have a significant contribution to the long-term efficacy of both drugs [18, 19]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Narula et al. demonstrated through the analysis of non-RCTs that IFX was associated with a lower 12-month colectomy rate compared to CyA, although no differences were found in the 3-month colectomy rate [20]. One could hypothesize that this could be related to a longer persistence of IFX as it is used as induction and maintenance therapy as opposed to CyA which is only used for induction, with patients usually transitioned to azathio-prine in the past. In the CONSTRUCT trial, after 12 weeks of follow-up, all treatments were at the discretion of the physician and only less than half of the patients were started on immunosuppressants in both groups [12]. Also, in the long-term follow-up of the patients in the CYSIF trial, a higher proportion of patients initially treated with CyA required subsequent systemic therapies when compared with those who received IFX at inclusion, with nearly half of patients first treated with CyA needing to switch quickly to IFX, within 1 year. After a median follow-up of 5 years, no differences were found between colectomy-free survival rates (61.5% vs. 65.1% for CyA and IFX, respectively, p = 0.97), although they were relatively higher when compared with the CONSTRUCT trial where the maintenance treatment was left at the discretion of the practising physician [12, 19]. Apart from efficacy, most studies have demonstrated no differences in terms of safety between IFX and CyA, although CyA is known to be associated with minor side effects (hypokalaemia, hypocalcaemia, tremors, paraesthesia, malaise, headache, abnormal liver function tests, gingival hyperplasia, and hirsutism) and with some major complications that despite being uncommon can be severe (hypertension, nephrotoxicity, opportunistic infections, and neurotoxicity) [21].

Salvage Therapy for IFX-Experienced Patients

CyA as a Salvage Therapy Followed by Non-Anti-TNF Biologics for Maintenance

In many countries, IFX has been chosen as the first-line salvage therapy for patients with steroid-resistant ASUC due to its ease of use, potential for transitioning to maintenance therapy, and extensive experience with the drug. However, CyA represents a valuable and cost-effective alternative, especially for patients with contraindications to anti-TNF therapy or those who have previously failed IFX. Limited studies directly address the use of CyA in ASUC patients previously exposed to IFX, with most evidence focusing on sequential rescue therapy with both drugs in the same ASUC episode.

In one study of 40 patients on sequential rescue therapy, the colectomy-free survival rate was 65% at 1 month and 42% at 1 year, despite 40% of patients experiencing adverse events that did not worthy discontinuation of the drug [22]. Another recent review of 81 patients demonstrated a colectomy-free rate of 42%[23]. While these results seem promising for avoiding colectomy in a specific group of patients, the overall colectomy rate remains high, and there are significant adverse events. Caution is advised when considering this strategy, given the limited and heterogeneous evidence based on small patient numbers.

However, patients requiring sequential rescue therapy with either CyA or IFX during the same episode of ASUC likely represent a more challenging group with a more severe form of the disease and a higher risk of adverse events. This differs from patients who previously experienced a loss of response to IFX and then developed ASUC. It is plausible that using CyA in this context could yield more positive outcomes, but additional data are necessary to confirm this, particularly regarding safety.

It is important to note that CyA should only be used when serum level measurements are available and as a bridge to other maintenance therapy. Azathioprine is the most well-established maintenance therapy in these cases. However, in the long term, azathioprine is poorly tolerated in many patients, it can be associated with an increased risk of malignancy (particularly in older patients and without previous exposure to the Epstein-Barr virus), and in patients who have been previously exposed to IFX, it may be insufficient as a maintenance therapy. Therefore, in patients with steroid-refractory ASUC who have previously failed IFX and who are now rescued with CyA, other maintenance therapies are needed.

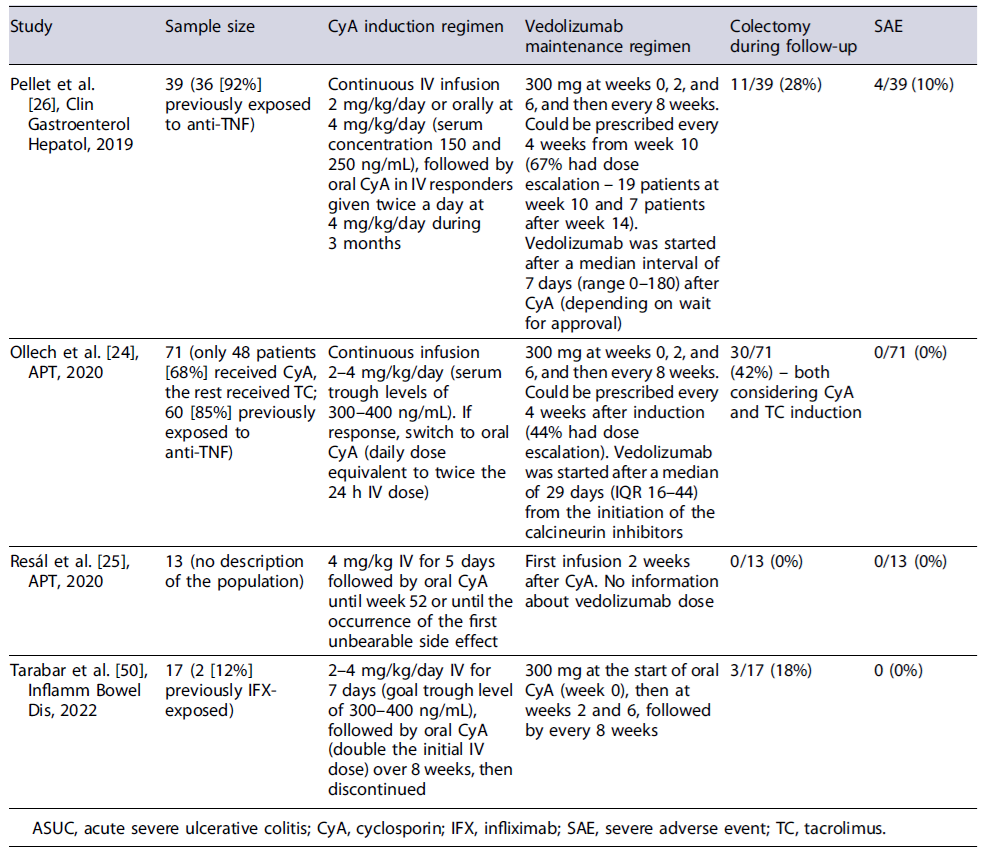

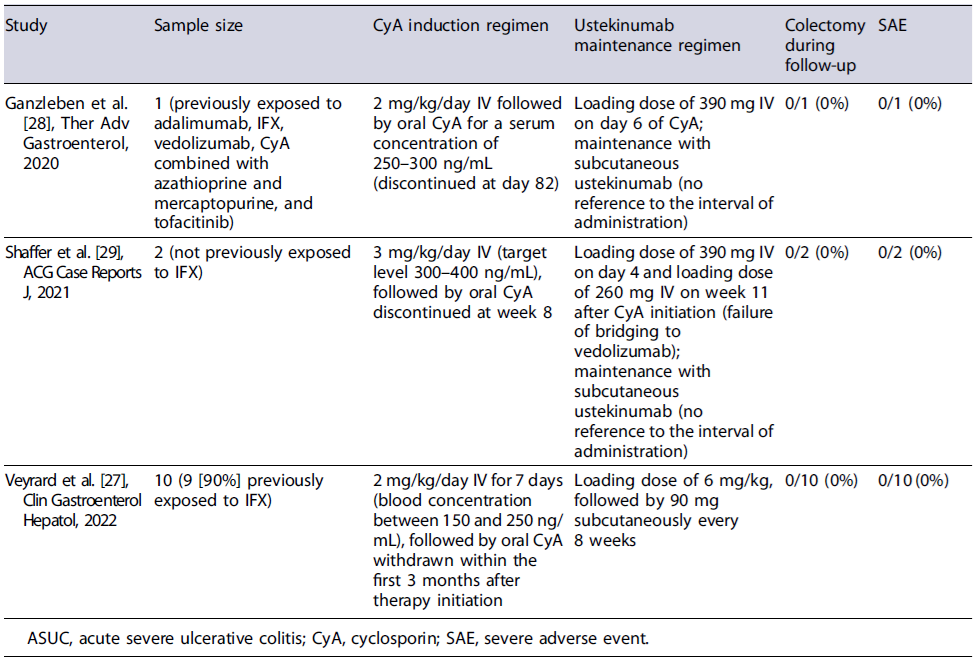

Data on the use of CyA followed by maintenance with vedolizumab or ustekinumab are scarce and mostly retrospective. In three studies with variable sample sizes, with different CyA induction regimens and with different timings of initiation of vedolizumab, the use of CyA for induction followed by maintenance with vedolizumab allowed more than two-thirds of the patients to avoid colectomy at 1 year of therapy without significant safety issues [24-26]. In a small prospective trial of 17 patients who received induction therapy with CyA and were maintained with vedolizumab, the colectomy-free survival at 1 year was 82% and 71% were in endoscopic remission by week 52 (shown in Table 1). Despite the heterogeneity in study groups, in a recent review, where only those patients fulfilling the ASUC criteria were considered, the colectomy-free rate was still high (71%)[23]. Regarding the bridging to ustekinumab, the evidence is even more scarce, being mostly of retrospective nature with low sample sizes (shown in Table 2). However, the results seem promising with none of the patients needing colectomy during follow-up [27-29].

Therefore, both vedolizumab and ustekinumab may become future maintenance therapies following induction with CyA in ASUC, with a more favourable safety profile when compared with thiopurines and being a reasonable option when patients have already failed anti-TNFs. Further prospective RCTs are needed to assess which therapy should be preferred, and what is the best timing to initiate the bridging following induction and to evaluate the long-term outcomes of these strategies.

Tacrolimus as an Alternative Calcineurin Inhibitor

Tacrolimus (TC) is a calcineurin inhibitor with a more potent inhibitory effect on activated T cells compared with CyA and with good bioavailability even when administered orally that can be used as an alternative therapy in patients with severe steroid-refractory UC. The first randomized study to elucidate the role of TC as an oral therapy for hospitalized patients with ASUC was published in 2006 and demonstrated that there was a dose-dependent efficacy and safety of oral TC with an optimal treatment target between 10 and 15 ng/mL [30]. In 2016, a systematic review with meta-analysis including 2 RCTs and 23 observational studies demonstrated that in severe and steroid-refractory UC patients, TC was associated with short-term high-clinical response and with colectomy-free rates that were as high as 70% after 12 months of follow-up, without increased risk of severe adverse events [31]. Also, a systematic review and network meta-analysis combined with benefit-risk analysis to simultaneously compare the efficacy (clinical response and colectomy-free rate) and safety of different therapies in severe steroid-refractory UC found that IFX was the most effective therapy, followed by CyA, TC, and placebo, though the differences between the three agents seemed small, suggesting also a role for TC in this setting. However, these results need to be interpreted with caution as there is no mean to statistically assess the difference between the benefits-risk of each therapy [32]. Also, most studies focus on outpatients with moderate-to-severe UC and, thus, there are insufficient data on the role of TC in ASUC patients. Moreover, most of the studies have a small follow-up of 2-4 weeks and there is scarce evidence on the long-term benefit of TC, particularly in reducing colectomy rates.

The Role of Janus Kinase Inhibitors in ASUC

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors like tofacitinib (OC-TAVE), filgotinib (SELECTION), and upadacitinib (U-ACHIEVE and U-ACCOMPLISH) are rapidly acting oral small molecules that have been approved for use in UC. They have different selectivity, with tofacitinib acting mostly on JAK 1 and JAK 3 receptors and filgotinib and upadacitinib with a more selective inhibition of JAK 1 receptor [33-35]. Several characteristics make JAK inhibitors attractive drugs in this setting, namely, their rapid onset of action and rapid clinical response with significant reduction by day 3 of baseline stool frequency sub-score, total number of daily bowel movements, and rectal bleeding sub-score when compared with placebo [36]. Their short half-life also leads to a rapid clearance, which may be relevant in the case of foreseeing colectomy, with a theoretical benefit in reducing perioperative complications. Moreover, as small molecules, they are less susceptible to drug loss, due to hypoalbuminemia and colonic protein loss, when compared to biologics.

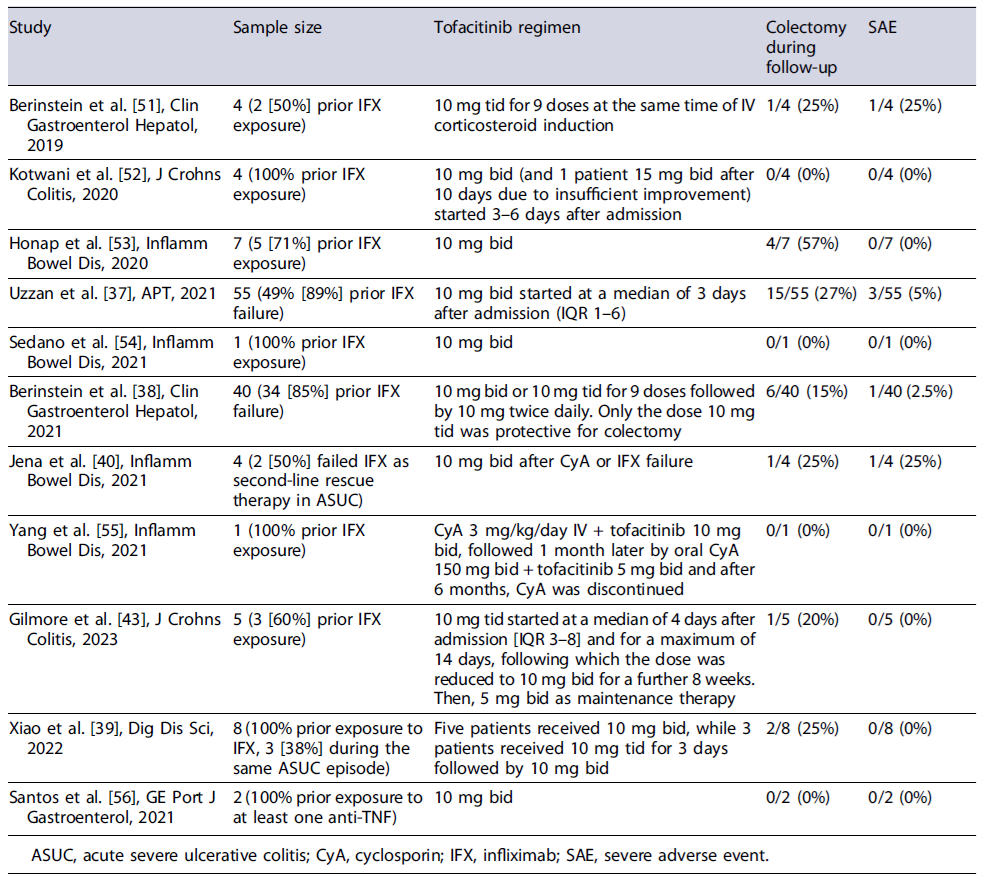

Tofacitinib has been the JAK inhibitor most frequently described in case reports and in a few case series and retrospective case-control studies as a rescue therapy in ASUC (shown in Table 3). To date, the largest report on the use of tofacitinib in ASUC included 55 patients who received 10 mg of tofacitinib bid and demonstrated a colectomy-free survival of 78.9% (95% CI 68.5-90.9) and 73.6% (95% CI 61.9-87.3) at 3 and 6 months, respectively. Despite these promising results, this study has a major limitation of not having a comparison group [37].

A retrospective case-control study performed by Berinstein et al. [38] included 40 biologic-experienced patients admitted with ASUC treated with intravenous steroids and tofacitinib which were matched 1:3 to controls (n = 113) according to gender and date of admission. Using Cox regression analysis adjusted for disease severity, tofacitinib was protective against colectomy at 90 days (HR 0.28, 95% CI 0.10-0.81, p = 0.018), although this result was only significant for patients taking tofacitinib 10 mg tid (HR 0.11, 95% CI 0.02-0.56, p = 0.008) [38]. Despite being the larger study with a comparison group, it is important to highlight that this work only focused on the role of tofacitinib as an adjuvant of corticosteroid therapy in inducing remission in biologic-experienced patients hospitalized with ASUC and did not assess the role of tofacitinib as a rescue therapy for steroid non-responders. Namely, in the control group only 39.8% of the patients needed a rescue therapy, which means that most patients responded to steroids. Furthermore, some case reports and case series have also explored the possible role of tofacitinib as a second-line rescue therapy in patients who have failed IFX, with a colectomy-free survival at 6 months of 62.5%[39]. In a systematic review of 21 patients with ASUC, tofacitinib demonstrated an efficacy of 75% (3/4) as first-line therapy, 85.7% (12/14) as second-line therapy (steroid failure), and 66.6% (2/3) as third-line therapy [40]. In another more recent systematic review including 148 reported cases using tofacitinib as second-line treatment after steroid failure in previous IFX failures or third line after sequential steroid and IFX or CyA failure, the 30-, 90-, and 180-day colectomy-free survival was 85%, 86%, and 69%, respectively [41]. Also, the ORCHID trial has recently demonstrated no differences on the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib for induction of remission in moderately active UC when compared with oral prednisolone [42]. Although there do not seem to exist significant safety issues with the use of tofacitinib in ASUC, some authors highlight possible concerns regarding a heightened risk of thrombosis in this setting and infectious risk, particularly herpes zoster infection [40, 41].

There was a significant heterogeneity across published studies in the dose of tofacitinib used to induce remission ranging from 20 to 30 mg/day in two to three divided daily doses. The study by Berinstein et al.[38] raised the possibility that only higher daily doses of 10 mg tid were effective in reducing the risk of colectomy [38]. Larger, prospective, RCTs are needed to clarify the safest, optimal dose, frequency, and duration of JAK inhibitor therapy in ASUC. In the meantime, it should be well noted that the use of JAK inhibitors in patients with ASUC that have previously failed IFX and are not responding to intravenous steroids is off-label, and probably should be reserved for referral centres with expertise in managing these patients.

One study (TRIUMPH trial, NCT04925973) is cur-rently ongoing and is recruiting patients with primary non-response or secondary loss of response to immunomodulators, anti-TNFα, anti-integrin, or anti-interleukin therapies or non-response after 3-7 days of intravenous steroids, which will be assigned to receive 10 mg bid of tofacitinib (single group assignment), and the primary outcome will be clinical response at day 7. One further trial (TOCASU trial, NCT05112263) expected to start recruiting soon intends to compare CyA with oral tofacitinib (10 mg tid for 3 days, followed by 10 mg bid for 8 weeks and then 5 mg bid until week 14) as first-line rescue therapies in steroid-refractory ASUC. These studies will hopefully provide further evidence on the role of tofacitinib as primary or sequential salvage therapy in ASUC.

Although with only very few case reports published, upadacitinib has also been suggested as a salvage therapy in patients with steroid-refractory ASUC, with the first study demonstrating that in 6 patients with prior loss of response to IFX, it allowed a colectomy-free rate of 83% after a follow-up of 16 weeks [43]. In a second report including 4 patients, only 1 patient needed colectomy, while half of them achieved steroid-free clinical and endoscopic remission after 3 months [44]. Similar to CyA, the efficacy of JAK inhibitors in IFX-experienced patients can only be extrapolated from case reports and more robust evidence is needed in the setting.

Treatment in IFX-Experienced ASUC Patients: Which Way to Go?

The widespread use of IFX as a primary salvage therapy in ASUC, and for those with moderate-to-severe UC unresponsive to standard treatment, has increased the number of individuals previously exposed to anti-TNF drugs. This growing cohort, along with patients exposed to other biologics and small molecules, poses a challenge in managing medical therapy for ASUC admissions. Previous studies have shown that patients with prior anti-TNF or thiopurine treatment, Clostridioides difficile infection, and high C-reactive protein or low albumin levels face a high risk of colectomy within a year [45]. Despite these complexities, avoiding emergent colectomy remains a goal due to its association with significantly higher mortality and morbidity [46]. However, the risks of emergent surgery need careful consideration in comparison with the risks associated with various immunosuppressive therapies and possible surgery delay due to prolonged medical therapy, contributing to increased surgical complications [47, 48]. A multidisciplinary approach, including timely assessment, surgeon consultation, and early nutritional evaluation, is recommended. Enteral nutrition should be the preferred choice, and recent studies propose a role for exclusive enteral nutrition as an adjuvant to corticosteroid therapy [49].

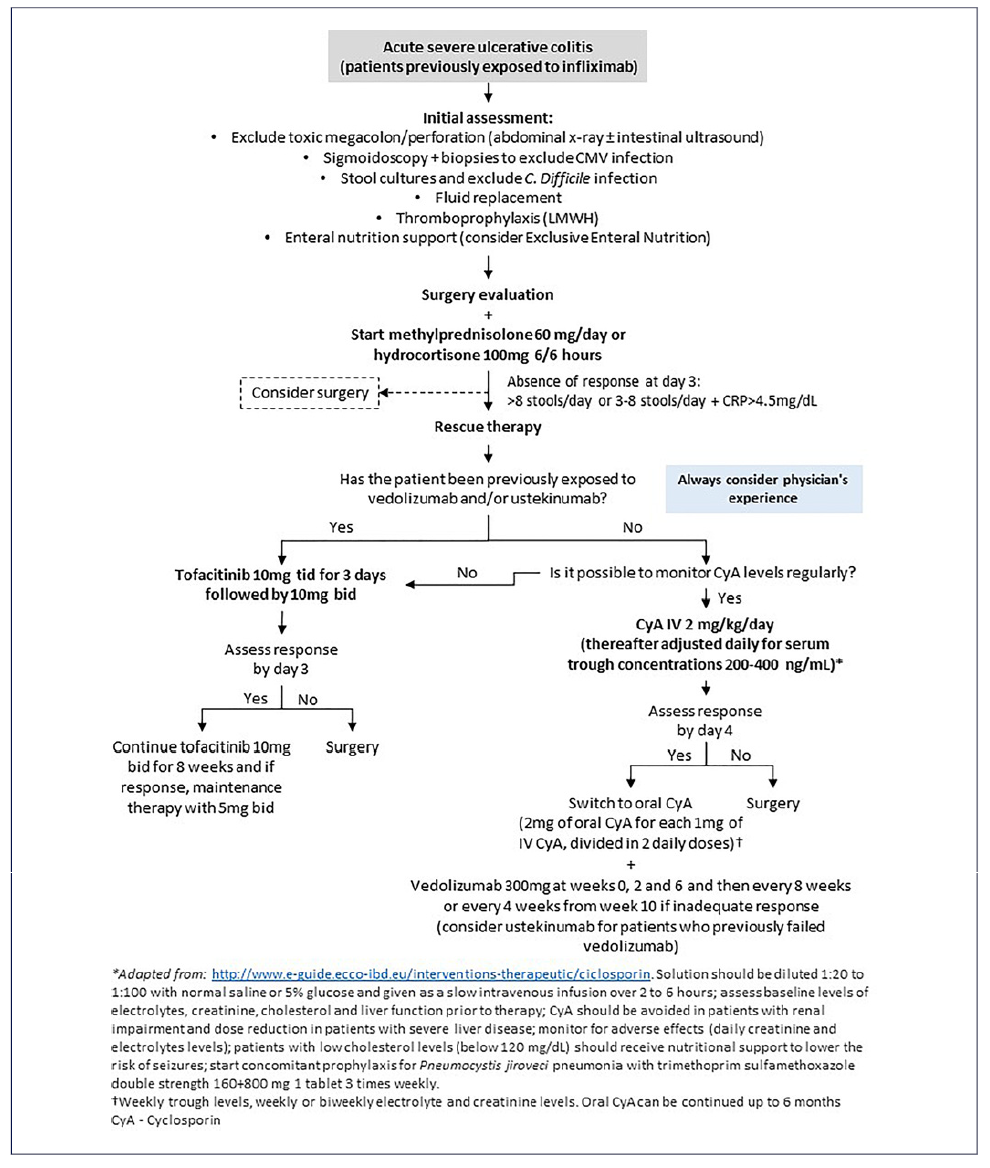

Based on the current revised data, two medical approaches may be considered for steroid-refractory ASUC patients who have lost response to IFX in the past. The first is to induce remission with CyA and then transition to another biologic such as vedolizumab or ustekinumab, and the second is to use tofacitinib for both induction and maintenance. Due to the lack of evidence, the choice between these strategies should rely on local policies, physician’s experience, and patient’s medical history. For example, in patients who have been exposed to ustekinumab and/or vedolizumab in addition to IFX, using a CyA-based strategy maybelimiteddue to the lack of an adequate maintenance therapy, making tofacitinib a potential option. A proposed algorithm of approach is shown in Figure 1. However, since evidence is limited, caution should be exercised when making this choice. The TOCASU trial’s results, comparing the efficacy of CyA and tofacitinib for steroid-refractory ASUC patients, will be relevant in this context. Other relevant unanswered questions include determining the preferred dose regimen for each drug, such as finding the most effective serum concentration for CyA and identifying the best dosing regimen for tofacitinib. Additionally, it is unclear whether tofacitinib should be initiated alongside steroids as a pre-emptive measure in patients who have failed IFX and it would be intriguing for future research to explore the prospect of initiating salvage therapy directly with this rapidly acting small molecules, circumventing the use of high-dose steroids, which can be associated with additional surgical risks. Furthermore, there is uncertainty about when it is appropriate to transition from intravenous CyA to oral CyA and when to begin maintenance therapy with CyA.

Fig. 1 Proposed algorithm for approaching steroid-refractory ASUC in patients previously exposed to IFX.

It is never enough to emphasize that ASUC is a serious condition with the potential for serious complications and that surgeons should be involved from the first day in complex decisions such as rescue therapy. Hence, it is imperative to handle IFX-experienced, steroid-refractory ASUC patients in specialized centres, under the guidance of a multidisciplinary medical-surgical team. Decisions should be collaboratively made with the patient, tailoring the approach to define the optimal treatment strategy for each unique case. The overarching objective is not merely to preserve the patient’s colon but, more significantly, to safeguard and enhance the patient’s overall well-being and life.

Conclusion

ASUC patients who are refractory to intravenous steroids and who have previously been exposed to IFX are a difficult-to-treat group of patients whose incidence has been increasing. Although the emergence of new biological and small molecule therapies is promising and has allowed the development of different salvage therapy algorithms, evidence is still scarce. Further RCTs are needed to define the best treatment for this group of patients, and surgery should always be considered.