Case Presentation

A 72-year-old man presented to our emergency department with progressively worsening abdominal pain over the past 2 weeks. His medical history included hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and bilateral hernia mesh repair. Additionally, the patient was managed on anticoagulant therapy with apixaban.

The pain was described as colic, more severe in the lower quadrants and not radiating. There were no associated symptoms of vomiting, nausea, anorexia, hematochezia, hematemesis or fever. However, the patient reported two episodes of transient loss of consciousness accompanied by prodromal sweating and dizziness. The patient mentioned a slight trauma while playing with his grandson the day before.

On admission, patient's vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 129/75 mmHg, heart rate 64 bpm, respiratory rate 18 bpm and body temperature was 36.5°C. Physical examination of the abdomen revealed mild left lower quadrant abdominal tenderness without guarding or rebound pain.

Laboratory tests were conducted which revealed a decrease in hemoglobin levels from 15.3g/dL to 10.7g/dL within 20 days, the white blood cell-count of 13.9x109 /L, a platelet count of 280x109 /L, an activated partial thromboplastin time of 25.3 seconds, an INR of 1.2 and a C-reactive protein level of 1.34 mg/dL.

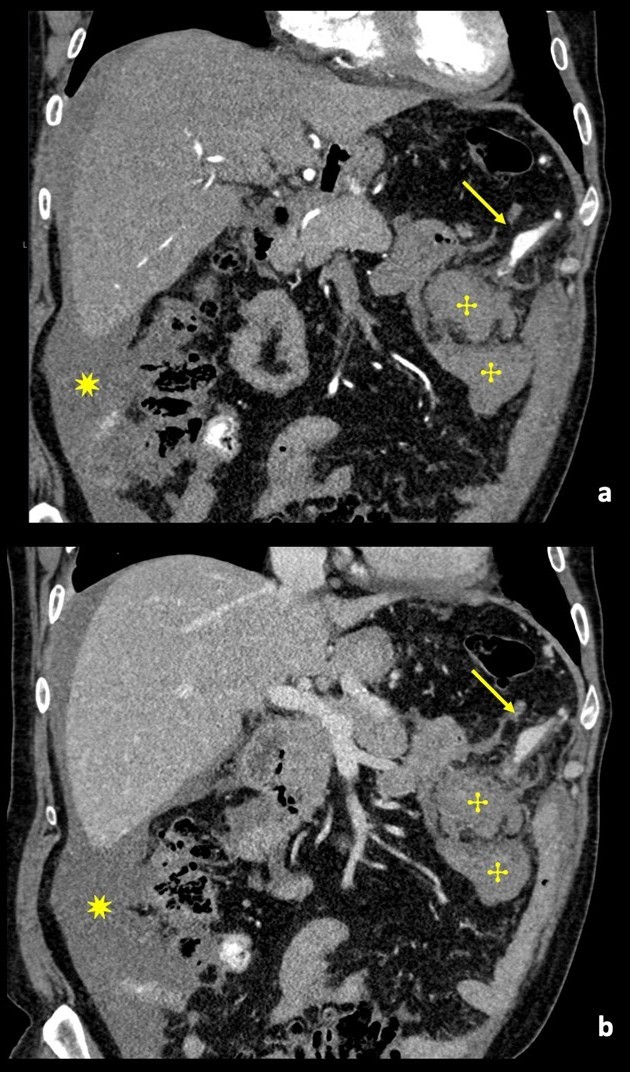

An enhanced CT of the abdomen showed high-density ascites with a moderate amount of blood and a hematoma on the left side of the omentum measuring approximately 5x5x4 cm in the longest axis in close proximity with a dilated and tortuous arterial branch of the gastroepiploic artery; there were no signs of active bleeding. The examination also revealed a fusiform dilatation of the celiac trunk (12mm of diameter). Additionally, the aorta displayed multiple atherosclerotic calcifications.(Fig. 1)

Figure 1: Contrast-enhanced coronal angio-CT reconstruction, in arterial phase (a) and venous phase (b), showing a multilobulated aneurysm sac (arrow) of the left gastroepiploic artery, without evidence of active hemorrhage. Adjacent to the aneurysmatic sac an intraperitoneal hematoma can be seen (✣). Hemoperitoneum (✷).

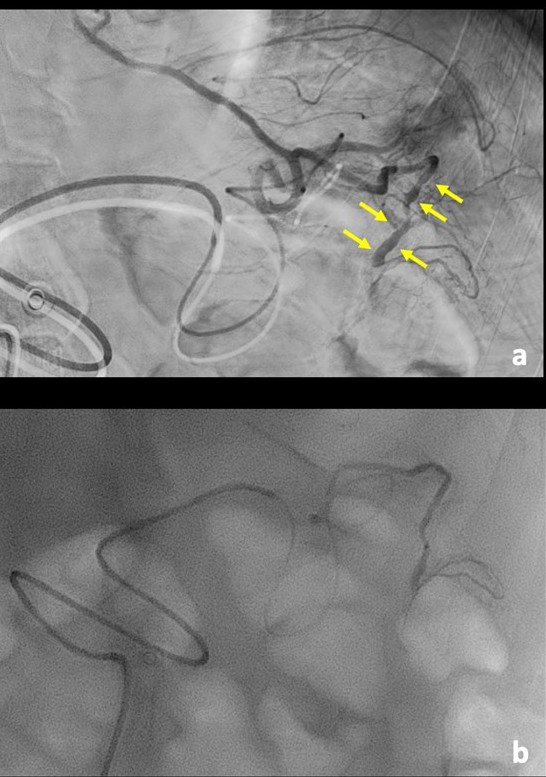

The diagnosis of ruptured aneurysm was suspected and an arteriography was performed, which showed ectatic and anomalous branches of the left gastroepiploic artery associated with mesenteric hemorrhage. The affected artery was successfully embolized with ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer, a liquid embolic agent. Hemoglobin remained stable in the early post-embolization period. The patient was discharged on the third day after the procedure.(Fig. 2)

Figure 2: Digital subtraction angiography (a), showing an ectatic and irregular left gastroepiploic artery (arrow). Because the angiography was performed with a day delay from the CT, the biggest aneurysmal sac is no longer seen, as it already thrombosed. Nevertheless, we decided to embolize (b) with liquid embolic (Squid®) the remaining abnormal artery, to prevent further complication.

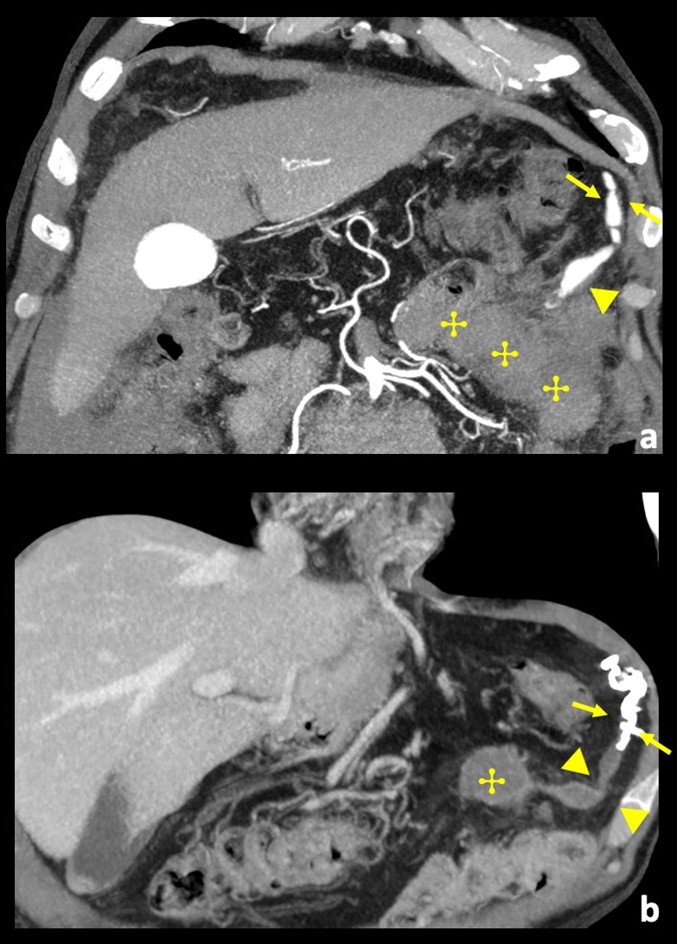

Figure 3: Comparison between contrast-enhanced coronal angio-CT MIP reconstruction pre-procedure (a), and, coronal image at the same level 1-month after embolization (b). (a) A long ectatic vessel with multilobulated aneurysms can be seen (arrow). (b) Corresponding image after embolization shows spontaneous thrombosis of the more distal and bigger aneurysmal sac (arrowhead) and hyperdense rich embolic material just upstream (arrow), corresponding to angiographic diagnostic image; there was hematoma re-absorption (✣), and there was no mass underlying.

One month after the procedure, the patient's hemoglobin increased to 12.8 g/dl. Follow up abdominal CT showed adequate embolization of the anomalous and ectatic segment of the left gastroepiploic artery, with hematoma retaining identical dimensions. The patient is under long-term outpatient clinical surveillance.(Fig. 3)

Discussion

Aneurysms of the gastric and gastroepiploic arteries are relatively rare, accounting for only about 4% of all visceral artery aneurysms.1,2,4

Their clinical presentation is diverse, ranging from asymptomatic cases to shock. Symptoms depend on the location and size of the aneurysm and may arise due to peripheral embolization, thrombotic occlusion, or compression of adjacent structures. The majority are symptomatic at the time of presentation and intermittent abdominal pain is the most common complaint.5

It is thought that atherosclerosis, collagen vascular disease, medial degeneration and fibromuscular dysplasia may all contribute to the formation of gastroepiploic artery aneurysms. Atherosclerosis, through a process that weakens the arterial media, contributes to the rupture of visceral aneurysms.6,7

CT angiography is the most used and sensitive non-invasive modality for the interventional management of aneurysms. An aneurysm will appear as a well defined contrast filled sac with attenuation parallel to adjacent main artery in arterial and venous phases. The CT will allow to assess anatomical arterial variations which will be necessary for planning the intervention. Imaging does not differentiate between a true and false aneurysm.8

Treatment options for gastroepiploic aneurysms depend on the patient's presentation, comorbidities and risk factors. Ruptured aneurysms require urgent management, with some cases requiring emergency surgery to ligate the aneurysm and resect the affected bowel segments.3 Overtime, percutaneous embolization has become a favored approach for healing many visceral aneurysms as technology and expertise in this area have advanced.

There are many different techniques and materials used for embolization, such as particles, gelfoam, coils, plugs, and liquid agents, The greatest risk of these procedures is distal ischemia or non-target embolization. These endovascular techniques have fewer complications than surgical intervention.9

The case we present had risk factors for ruptured aneurysms as arterial hypertension, visceral atherosclerosis, and anticoagulant therapy. There was no family history of visceral aneurysms. Although there was no history of major trauma, we can't rule out the possibility that the minor trauma in a hypocoagulated patient may have contributed to vessel rupture and pseudo-aneurysm formation.

Despite the significant drop in hemoglobin levels the patient remained hemodynamically stable. Percutaneous embolization was chosen as the treatment method and immediate imaging confirmed its effectiveness in controlling the active bleeding from the ectatic vessel of the left gastroepiploic artery. Subsequent follow up revealed an increase in hemoglobin levels and complete resolution of abdominal symptoms, validating the safety of initial minimally invasive treatment decisions.