Introduction

Primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNET) are a class of rare neurogenic small round and undifferentiated cell tumors which belong to the Ewing’s sarcoma family.1 They originate from neural crest cells found in bones and soft tissues and can occur in the central nervous system (cPNET) or in other peripheric organs (pPNET). However, they rarely occur in the colorectal tract and to our knowledge no more than 5 cases of rectal pPNETs were described.2 They represent 1% of all sarcomas, are highly aggressive and are related with a poor prognosis due to its highly metastatic potential and lack of efficient treatment options.3,4 We present the case of a male patient with pPNET of the rectum with an unusual presentation.

Clinical Case

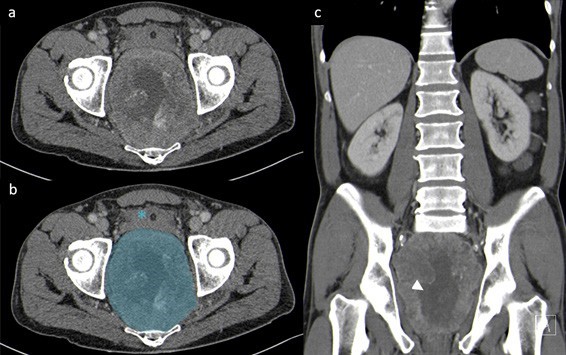

An otherwise healthy 54-year-old male presented to the emergency department with urinary retention and lower abdominal pain. He also had a history of constipation and weight-loss over 6 months. He denied rectal bleeding and his physical examination and blood tests were unremarkable. An abdominal ultrasound was performed and documented a retro-vesical heterogeneous mass. Computed tomography confirmed the presence of a soft-tissue pelvic mass that compressed the wall of the rectum and the bladder with 11,5 x 9,5 x 12,5 cm (antero-posterior x transverse x longitudinal) (Fig.1). There was no evidence of distant metastization.

Figure 1: Original (a) and annotated (b) axial CT and coronal reconstruction (c) in portal- venous phase, demonstrating an exuberant and heterogeneous mass adjacent to the rectum (blue), with central necrosis (white arrowhead). The bladder (asterisk), prostate and seminal vesicles (not shown) are pushed against the anterior abdominal wall.

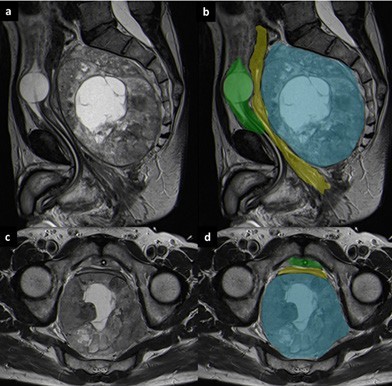

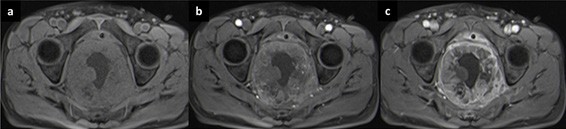

A colonoscopy was later performed and demonstrated an extrinsic compression of the rectal wall with a normal mucosa. Multiple biopsies were performed and the result was suggestive of a neuroendocrine rectal tumor. Laboratory tests showed an elevation of neuron-specific enolase (43.6 µg/L) and chromogranin A (6.2 nmol/L), with normal plasmatic metanephrines. MRI was also performed to plan surgical treatment (Fig. 2) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Sagittal T2-weighted (a and b) and axial T2-weighted MRI images (c and d). On MRI the lesion (blue) is well-demarcated and has a heterogeneous appearance, with a central necrotic area. It originates from the posterior wall of the rectum (yellow) and occupies the presacral space. The urinary bladder (green) is collapsed.

Figure 3: T1 FS-weighted images before (a) and after contrast enhancement in arterial (b) and late (c) phases. Note the heterogeneous and peripheral enhancement of the lesion, especially in the delayed phase (5 minutes after contrast administration).

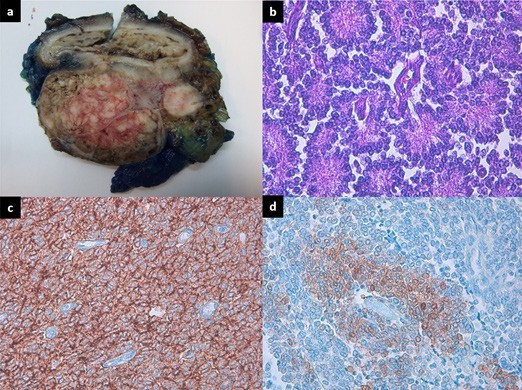

The patient was submitted to surgical resection and histologic findings and immunohistochemical studies were compatible with a rectal pPNET, with a proliferation index of 10% (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: (a) Gross picture of the rectal tumor, demonstrating no involvement of the mucosa. (b) High power view of the tumor cells showing uniform small round blue cells with scant cytoplasm and the presence of Homer-Wright rosettes (HE x 40). (c) Neoplastic cells showing strong expression of CD99 (immunohistochemical staining, × 40). (d) The tumor cells were positive for NSE in a cytoplasmic stain (DAB x 20).

Follow-up CT demonstrated multiple liver metastases only 4 months after diagnosis. A combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy was offered and one year after the diagnosis the patient remains with stable disease.

Discussion

Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumors are rare small round cell tumors which can occur in the brain, spine, kidney and in other soft tissue, but rarely in the colorectal tract.1,2,4 This case depicts an extremely rare location for pPNETs, as for our knowledge no more than 5 cases of rectal PNETs have been described in literature. They rarely occur in adults, more frequently affecting children and young adults.5

Peripheral PNETs can involve virtually any body part (except central nervous system). Clinical presentation varies depending on the site of involvement, but they typically appear as rapidly growing masses. In our case, main symptoms were non-specific like urinary retention, lower abdominal pain and constipation, due to compression of adjacent organs.

As pPNETs have no specific imaging findings, they are lately diagnosed. Peripheral PNETs appear more frequently as a large and ill-defined soft tissue mass with central necrosis and lytic bone destruction.6 They usually enhance heterogeneously after contrast administration, with varying areas of necrosis due to the rapid growth and lack of sufficient blood supply in the central area of the tumor.6 The extent of intratumoral necrosis correlates with the size of the tumor and is due to the rapid growth and lack of sufficient blood supply in the central area of the tumor.6 However, these findings are non-specific, making it almost impossible to differentiate these tumors from other malignant lesions. Differential diagnosis should be made with submucosal lesions of the rectum that may present as a mass, such as Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST) and neuroendocrine tumor. This way, pPNET diagnosis is a challenge due to the lack of specific symptoms, low incidence and the lack of specific imaging features. Despite this, CT and MRI can be used to evaluate local and metastatic disease, being helpful in staging, pre-operative planning and monitoring treatment.

Histologically, pPNETs typically demonstrate diffuse sheets of small cells with intervening fibrovascular stroma.7 Differential diagnosis should be made with small- cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, malignant lymphoma and rhabdomyosarcoma.6 In this case, diagnosis was established by histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of tumoral tissue, characterized by neuroectodermal differentiation with Homer-Wright rosette formations and strong expression of CD99+ and neuron-specific enolase.

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice when possible. However, results are frequently unsatisfactory, primarily due to the extent of the lesion and the appearance of distant metastasis.2 Consequently, treatment consists of a combination of surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Rectal pPNETs have bad prognosis, with the majority of patients deceasing 1-2 years after diagnosis.2 Only one long- term survivor of rectal pPNET is known, with a remission of 7 years following intensive chemotherapy, radiotherapy and stem cell transplant, before the development of anal carcinoma.8

In conclusion, pPNETs are generally rapid growing tumors that can involve any part of the body, generally with non-specific symptoms. Although there is a lack of typical imaging findings, a large ill-defined and aggressive soft tissue mass with heterogeneous enhancement on CT or MRI is suggestive. The diagnosis is histological and immunohistochemical and these patients have poor prognosis, even after surgical resection and chemotherapy. This patient had a pPNET with a low proliferation index, which can explain why he has stable disease one year after diagnosis.