Introduction

Sepsis is responsible for about 11% of maternal mortality globally1. In high-income countries, 5% of puerperal deaths are due to postpartum infections2. Few studies have analyzed the role of antibiotic prophylaxis after operative birth3. It is known, however, that operative birth, without prophylactic antibiotic therapy, is associated with postpartum infections in about 16% of the cases4. Compared with spontaneous vaginal birth, operative birth can be associated with longer labor, more vaginal examinations, bladder catheterization before the procedure, more perineal lacerations, and use of episiotomy, all of which can increase the risk of infection5.

After the publication of the ANODE trial, which demonstrated benefit in prophylactic antibiotic administration after an operative birth, there have been some changes in international recommendations on prophylactic antibiotic therapy6-11. However, it should be noted that women who underwent peripartum antibiotic therapy were included and that the study showed a high proportion of complications after operative birth, contrary to what is exposed in other studies12.

Despite limited data and the limitations of the ANODE trial, many professional societies (World Health Organization (WHO), the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RANZCOG) have changed their recommendations to include antibiotic prophylaxis following operative vaginal delivery. However, further studies are needed to understand whether operative birth may be an independent risk factor for postpartum infection. The main goal of this study was to compare the prevalence of infection after operative birth with spontaneous vaginal birth in a public and tertiary care hospital and find independent risk factors for postpartum infection.

METHODS

This was a prospective longitudinal observational study at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of a public tertiary hospital. Patients with a singleton vaginal birth at term were enrolled in this study from June 2020 until June 2021. Exclusion criteria for both groups were multiple gestations, preterm deliveries, breech birth, antibiotic therapy in the peripartum period, namely due to colonization by Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS), intrapartum fever, manual removal of the placenta, perineal lacerations of grade ≥ III or another non-obstetric indication for antibiotic therapy; Covid-19 positive patients were also excluded. A convenience sample in a 1:1 ratio (operative birth: spontaneous vaginal birth) was obtained, being collected the spontaneous vaginal birth that occurred immediately after an operative delivery included in the study. Sample size was calculated based on the incidence of puerperal infection described in the literature and from data of puerperal infection prevalence from our hospital, considering a drop rate of 15% (https://riskcalc.org/samplesize). As such, it was estimated that 376 patients were needed (188 operative births and 188 spontaneous vaginal births).

Study design and data collection

In the first 24 hours after birth, data were collected from direct interview and the clinical recordings containing sociodemographic data and relevant medical and obstetric history (including conditions related to immunosuppressive state), intrapartum parameters, neonatal data, and puerperal complications including anemia requiring correction with intravenous iron or transfusion. Labor related parameters were mainly duration of membrane rupture, duration of active labor (since 5-6 cm of dilation), spontaneous/induced labor, and perineal tears.

In a second phase, about 6 weeks after the birth, a brief telephone survey was carried out, questioning the occurrence of infection (perineal infection, endometritis, urinary tract infection or sepsis) requiring oral or intravenous antibiotic therapy and antibiotic prescription.

The primary outcome of this study was to determine the association of operative delivery and peripartum infection. Secondary outcomes were to find independent risk factors for postpartum infection.

Ethics and confidentiality of data

The present study was submitted and approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee for Research in Life and Health Sciences and the Data Protection Officer (Reference 20200054 _ Obstetricia 290420). All participants signed informed consent forms to participate in the study. A code was attributed to each participant to ensure data confidentiality and this code was used to compile the different survey replies at each time point. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments in Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, in the International Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies of the International Medical Science Organizations and the Guide to Good Clinical Practice (ICH, GCP).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences® (SPSS) program, version 27.0. Statistical analysis included a descriptive and inferential analysis of the data by type of birth. Then, postpartum infection was analyzed to search for risk factors and predictors of it. Continuous variables with normal distribution were analyzed using the mean and standard deviation (SD), and variables without normal distribution were analyzed according to the median and the interquartile range (IQR); categorical variables were presented with frequencies and percentages. Chi-square and Fischer exact test were used for categorical variables, while independent sample t-test or the Mann-Whitney Test were used for continuous variables, when variables assumed a normal distribution or not, respectively. As measures of effect size, when Student’s T and Mann-Whitney tests were used, the values of Cohen’s d (d) and r (obtained from z) were analyzed, respectively. Regarding the Chi-Square tests or Fisher’s Test, the phi coefficient (φ) was used for 2 x 2 tables, and Cramer’s V (φc) for n x n tables. For all tests, the cohort points considered were low (0.1), moderate (0.3) and high (0.5), apart from Cohen’s d, in which the cohort points were low (0.2), medium (0.5) and high (0.8). To assess the contribution of a set of predictors to the occurrence of postpartum infection, a binary logistic regression model was used. The predictors studied were those with a significant association in the bivariate analysis and the ones described in the literature. A p value <0.05 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) were considered statistically significant.

Results

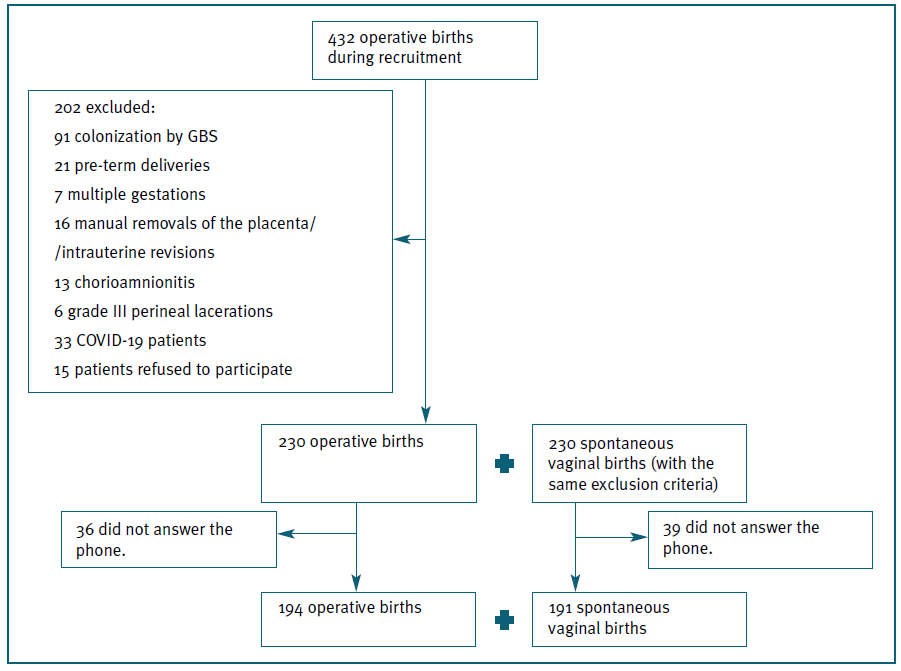

During the study period there were 432 operative births, of which 230 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. As such, data were collected also from 230 spontaneous vaginal births. Of these, 36 operative births and 39 spontaneous vaginal births (15.6% and 16.9%) were lost because women did not answer the phone in the postpartum period. Therefore, a total of 385 postpartum women were included, 194 in the operative birth group and 191 in the spontaneous vaginal birth group (Figure 1).

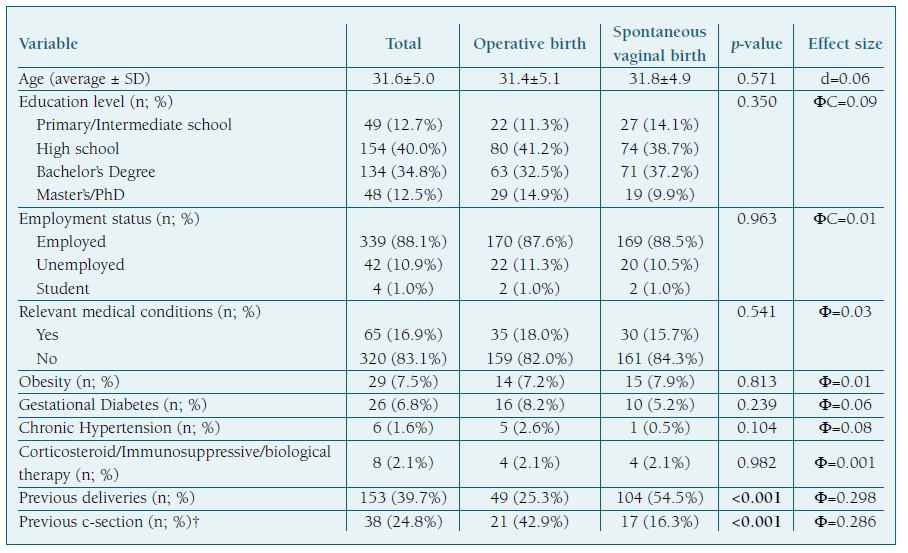

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table I, stratified by type of delivery. No statistically significant differences were found between the two types of delivery regarding to sociodemographic characteristics and past medical history. Concerning obstetric history, there was a significant difference between the groups regarding parity, with the operative birth group including a larger proportion of primiparous (74.7% versus 45.5%; p<0.001) and the rate of previous caesarean section was also significantly higher in this group (42.9% versus 16.3%; p<0.001) (Table I).

Of the operative births, 122 were obstetric vacuum (Kiwi®), 14 were Simpson forceps and 58 were Thierry spatulas. Regarding the reasons for the operative births, the majority were carried out because of prolonged second stage of labor (85); followed by suspicion of immediate or potential fetal compromise (47), maternal exhaustion (42) and shorten the second stage of labor (20).

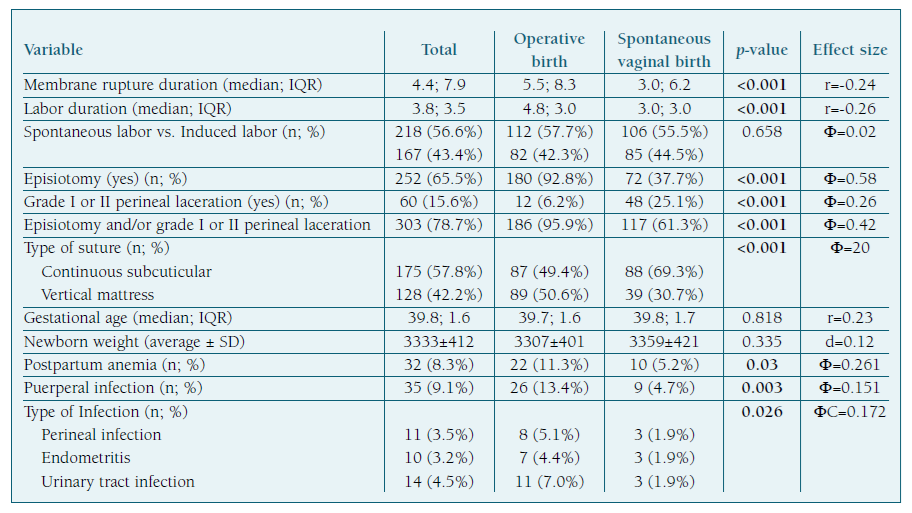

The two types of vaginal birth differed in some parameters related to labor (Table I). Parturients with operative birth had a median duration of ruptured membranes and labor longer than women with spontaneous vaginal birth (5.5 hours versus 3.0 hours, p<0.001; 4.8 hours versus 3.0 hours, p<0.001). There was also a higher rate of episiotomies in the operative birth group compared to the spontaneous vaginal birth group (92.8% versus 37.7%; p<0.001). In turn, the occurrence of grade I or II perineal lacerations was more frequent in spontaneous vaginal births (25.1% versus 6.2%; p<0.001). Even grouping episiotomy and perineum lacerations, to compare the occurrence of perineal tears or not, there was a statistical difference (operative birth 95.9% versus spontaneous vaginal birth 78.7%; p<0.001). Finally, there was a greater tendency towards continuous suturing in the spontaneous vaginal birth compared with operative birth (69.3% versus 49.4%; p<0.001). No differences were found regarding other labor parameters and newborn outcomes.

Even though both anemia and puerperal infection were rare, with only 8.3% anemia and 9.1% postpartum infection, both complications were more common in operative birth compared to spontaneous vaginal birth (11.3% versus 5.2%, p=0.03; and 13.4% versus 4.7%, p=0.003, respectively) (Table II). Urinary tract infection was the most prevalent infection in operative birth group (7.0%), followed by perineal infection (5.1%) and endometritis (4.4%), whereas in spontaneous vaginal birth group they were all present at a similar rate (1.9%) (p=0.026) (Table II ).

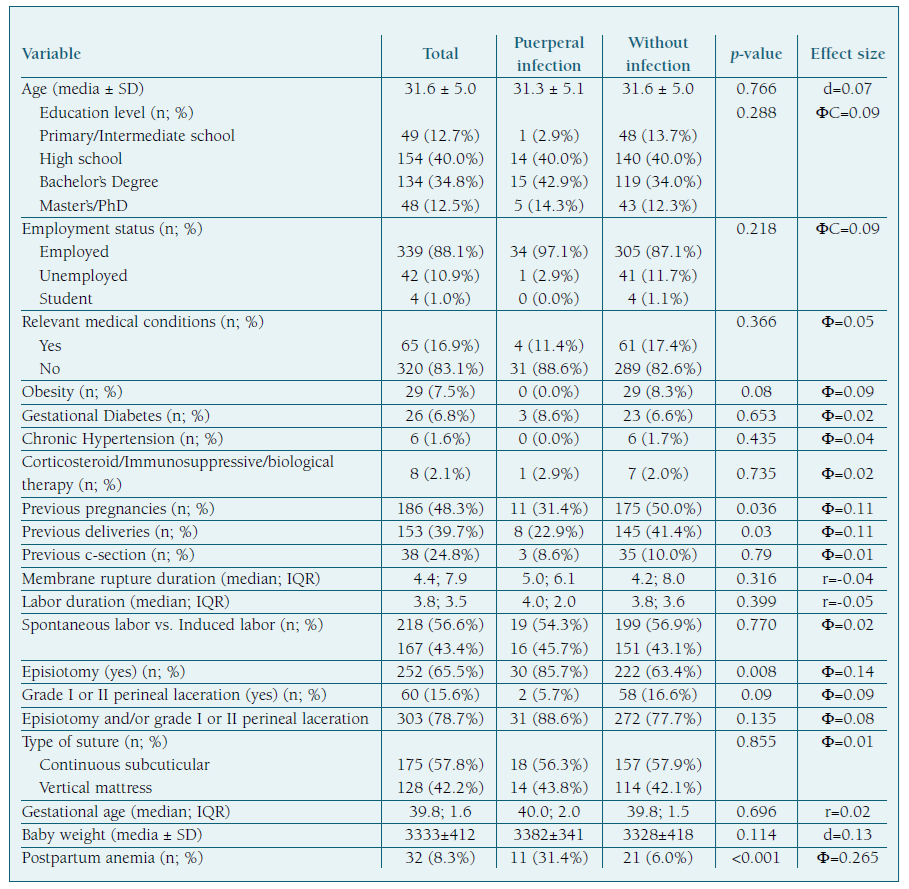

To understand if puerperal infection, which showed a statistically significant difference between the two types of birth, was associated with other factors, a bivariate analysis was performed (Table III). Postpartum infection was significantly associated with first pregnancies (p=0.036), nulliparity (p=0.03), episiotomy (p=0.008) and postpartum anemia (p<0.001).

Finally, a regression model for the prediction of infection was created based on the variables with statistically significant results and the ones described in the literature, such as maternal age, education level, employment status, duration of labor and membrane rupture, obesity, and hypertension. The regression model was statistically significant (p<0.001; R2 Nagelkerke = 0.210; R2 Cox & Snell = 0.096; correctly predicted cases percentage = 90.8%). Anemia remained the only significant predictor, being associated with a 5.6-fold increase in the likelihood of postpartum infection (p<0.001).

Discussion

Principal findings

Postpartum infection remains an important cause of mortality, globally1),(2. In this study, postpartum infection occurred in 9.1% of cases; in the bivariate analyses it was more frequent in operative birth than spontaneous vaginal birth (13.4% vs. 4.7%), which comes along with the current discussion about the role of antibiotic prophylaxis13.

Results in the context of what is known

Operative birth is being described as a risk factor for the development of infectious complications in different studies12),(14-18. Several studies point to age as a risk factor for postpartum infection, although there is controversy as to which age (older or younger) is associated with increased risk. In the present study no statistical difference was found15),(17),(19. Education level and employment status (indicators of socioeconomic status) did not show differences between groups, contrary to what was found by other authors, who report association of maternal sepsis with poor socioeconomic parameters19. There was a higher proportion of nulliparous women in the group with infection (77.1 % vs. 58.6%), which is in line with what is reported in the literature14),(19. It is well established that prolonged labor and membrane rupture are related to an increased risk of infection, but in this study we did not find such association, maybe because of careful hospital surveillance and working in accordance with hospital infection control standards20),(21. Also, it is important to recall that intrapartum fever cases and women to whom antibiotic was administrated were excluded. There was no relationship between the occurrence of infection and perineal lacerations, a situation that can be explained by the fact that one of the exclusion criteria was perineal lacerations of grade ≥ III, being these the ones most associated with infection17),(22. Like in another study, type of suture did not differ between groups23. There was a higher proportion of episiotomies performed in the group that developed puerperal infections (85.7% vs. 63.4%), which is corroborated by what is described in the literature and could support ACOG guidelines9),(17),(22),(24. On the other hand, this also may be related to the bigger proportion of episiotomies performed in operative birth group and a confounding effect, as explained later, since both are associated with puerperal infection in bivariate analyses only. Postpartum anemia was significantly related to the occurrence of infection (31.4% vs. 6.0%). This result is also documented in the existing literature, although the mechanism of this association is not yet understood15),(17. Several of the studied factors in this study may be interconnected, such as anemia, instrumental delivery and perineal tears.

There is no consensus in the literature regarding the impact of operative birth on the occurrence of infection, since it is presented as a risk factor in some studies, but not in others12),(14-19),(25. However, in most of these studies the statistical analyses are performed not considering major confounding factors, such as the occurrence of perineal laceration or episiotomy13. The present study found that the type of birth was not an independent risk factor when such factors were included in the multivariate analysis. Thus, despite the significant association of nulliparity, operative birth, episiotomy, and postpartum anemia with the existence of infection, when the binary logistic regression model was created, only anemia remained as an independent predictor. Even including other variables described in the literature (maternal age, education level, employment status, obesity, hypertension, duration of labor and rupture of membranes), only anemia remained an independent factor associated with postpartum infection15),(17. Furthermore, the results of this study highlight the significance of peripartum anemia. Considering that the aim of this study was to find associations between different factors and postpartum infections, which may assist clinicians in identifying women at high risk for infection, reduction of this complication is of great importance in the prevention of postpartum infectious morbidity.

Clinical implications

Although the ANODE study showed evidence of the benefit of prophylactic antibiotic therapy after operative birth, the high number of complications observed in that study must be considered12. Furthermore, the only infections that occurred in a significantly lower proportion in the group that received antibiotics, were those directly related to the surgical wound, for which the main risk factors are episiotomy and perineal lacerations and not the operative birth itself. Major international societies changed their recommendations based solely on ANODE study, but our local investigation showed different results6-8. This is relevant for clinical practice and local protocols, as defended in WHO recommendations, which stands by the establishment of local protocols, infection surveillance and clinical audit and feedback. As part of the global efforts to reduce antimicrobial resistance, antibiotics should be administered only when there is a clear medical indication and where the expected benefits outweigh the potential harms within the local context8.

Research implications

Since this is still a debatable question, before considering the generalization of antibiotic prophylaxis, maybe each hospital needs to analyze their own data and think about how to control other risk factors.

Strengths and limitations

This prospective analysis reduces the occurrence of a memory bias typical of retrospective studies. About the limitations, since postpartum anemia was an independent predictor of puerperal infection, it would have been important to identify women with anemia prior to delivery and how this variable could or could not influence the infection rate. Additionally, sample size is one limitation of the study, although it was within the estimated necessary size for validated results, it can influence the low prevalence of postpartum infections and makes it difficult to generalize results.

Conclusions

The conclusions of the present study reiterate the need to continue the investigation of operative birth contribution to postpartum infection. There is an urgent need to clarify the risk factors for puerperal infection and then build decision algorithms that allow an individualized approach, based on the risk of each patient. It is also important to think about the burden of antibiotic resistance related to exaggerated antibiotic prescription. Considering all these factors, studying our local data is essential for making good decisions for our patients.

Author contributions

MFC, RS, MC e CNS contributed to the concept and study design. All authors contributed to data curation, analysis and interpretation of data. MFC and RS were responsible for the article draft. CNS supervised the team research and revised the article critically. All au-thors approved the final article as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.