Introduction

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry states that “dental care is medically necessary for the purpose of preventing and eliminating orofacial disease, infection, and pain, restoring the form and function of the dentition, and correcting facial disfiguration or dysfunction.”1 Some studies have shown that underlying medical and mental health conditions can affect both the severity and treatment approaches of dental disease, sometimes requiring modifications to standard protocols.2-4

General anesthesia (GA) use for dental procedures is increasing in pediatric patients with and without special healthcare needs.3,5,6 Non-pharmacological behavior guidance techniques are frequently used when treating children and adolescents, including those with special needs.7 However, occasionally, pharmacological techniques such as moderate or deep sedation are required in patients unable to cooperate.5,6,8-10

Epidemiological studies in Spain have shown a decreased frequency of caries and periodontal disease-the main oral pathologies across age groups. An oral health survey conducted in 2020 showed that 28.6% of 12-year-olds and 35.5% of 15-year-olds in Spain had caries in permanent teeth. These rates were significantly lower than the respective rates of 68.0% and 55.0% found in a similar survey conducted in 1993.

The improvements could be linked to the introduction of universal dental care programs for children in 1998.11 We did not find similar studies that assessed the treatment modality used in patients with special healthcare needs. GA is an effective sedation method for children undergoing dental procedures. However, it often results in post-operative symptoms, such as pain (sometimes requiring painkillers), drowsiness, inability to eat, bleeding, agitation, cough, fever, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, sleep disturbances, and weakness. The most common symptom is mild to moderate pain.12-14

Few studies have analyzed alternatives to GA.8,15-17 While basic behavior guidance may be effective in patients with behavioral difficulties, it has low success rates in patients with special healthcare needs.10 Conscious sedation (CS) with nitrous oxide, alone or combined with benzodiazepines, is the most widely used technique and is often attempted before GA. It is considered safer and has been linked to fewer post-procedural complications.16

More studies are needed to understand the characteristics, effectiveness, and potential complications of surgical procedures in dental patients with special needs, who vary significantly depending on age, comorbidities, behavior, and risk of oral pathologies. In our setting, most children receive dental care under local anesthesia (LA) in primary care pediatric dental care units. In contrast, children with special healthcare needs, including those with difficulty cooperating for various reasons, are referred to our hospital for treatment under GA or LA with or without CS (LA/LA+CS). We undertook a study to review our experience and compare the effectiveness/success and complications of GA and LA/LA+CS in pediatric dental patients undergoing comparable minor surgical procedures.

Material and Methods

We conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional study based on an electronic chart review of pediatric patients who underwent minor oral surgery under GA or LA/LA+CS in the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (OMFS) Department of Hospital Clínico Universitario in Valencia, Spain, between 2017 and 2019. The study was approved by the hospital’s clinical research ethics committee (ref. 018/207). The specific aims were to compare the effectiveness/success of comparable procedures according to whether they were performed under GA or LA/LA+CS and to explore associations between the two techniques and general patient and health-related characteristics.

We studied consecutive patients referred to the OMFS department who met the following inclusion criteria: ages of 0-15 years; caries diagnosis, unerupted teeth, or other conditions requiring minor oral surgery; difficulty cooperating for various reasons; and use of GA or LA/LA+CS. Patients who underwent complex maxillofacial procedures such as craniosynostosis surgery were excluded to avoid possible information bias originating from the overrepresentation of patients with more complex conditions and a higher risk of poor functional outcomes.

The primary outcome was procedural effectiveness/success, defined as treatment completion without major complications other than mild pain (≤2 on the WHO scale).18 It was recorded as a binary variable. The type of anesthesia-GA or LA/LA+CS-was the main predictor variable. The following were additional predictors and potential confounders: age; nationality; sex; reason for referral; dental diagnosis; American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification; reason for choice of anesthesia; duration of hospital admission, anesthesia, and surgery; type of treatment; complications; and preventive treatment.

Secondary outcomes were surgical and intraoperative morbidity. Surgical morbidity was defined as any adverse effects or complications experienced by the patient after regaining consciousness and being able to breathe unaided (e.g., nausea). Intraoperative morbidity was defined as any complications that occurred during the procedure and required the intervention of the anesthesiologist or the administration of drugs (e.g., respiratory arrest).19

A single researcher (ALV) recorded the study variables in a protected, purpose-designed Excel sheet following a standardized procedure. A second researcher (PVF) subsequently reviewed the entries to reduce the risk of information bias arising from data collection.

Statistical analysis was performed. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation, and categorical variables were expressed as percentages with a confidence interval of 95%. Comparisons were made using the t test for continuous variables and the χ2 or Fisher exact test for qualitative variables. The Mantel-Haenszel trend test was used for variables with several categories. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for non-normally distributed data.

Differences in procedural success according to the use of GA or LA/LA+CS were analyzed using the t test. Binary regression analysis was used to identify possible interacting and confounding factors. Confounders were selected based on a change-in-estimate >10%,20 or a clinically significant change,21 after applying the iterative algorithm proposed by Doménech and Navarro.22 Residual analysis was then performed to assess independence, homogeneity of variances, collinearity, and the presence of values that exert an influence.

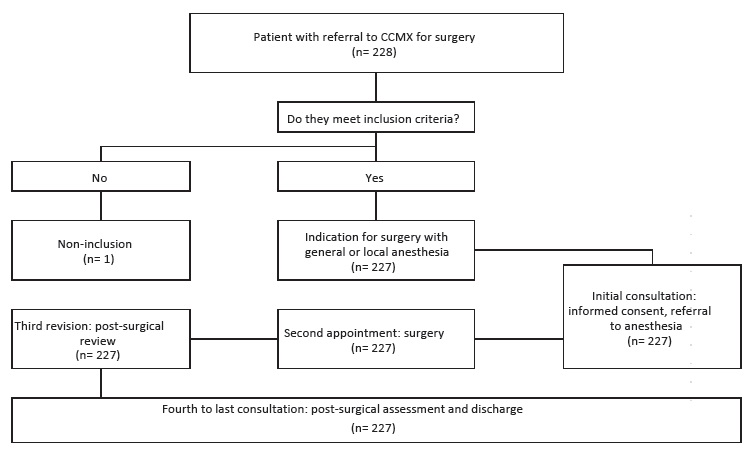

Odds ratios were reported with 95% confidence intervals. Statistical significance was set at 0.05 in all cases. All analyses were performed in STATA 17 (StataCorp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. College Station, TX: StataCorpLLC). Data from initial visits, surgery, first follow-up appointments, and discharge reports were collected for 192 children who underwent 227 procedures. One child was excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Results

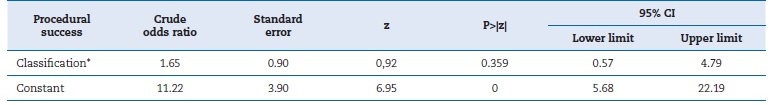

Table 1 summarizes the results for the main study variables. Mean age was 9.50 years (95% CI: 8.83-10.18) in the GA group and 10.18 years (95% CI: 9.48-10.88) in the LA/LA+CS group (range, 0-15 years in both cases). There were more boys than girls in both groups: 52.14% vs. 42.73% in the GA group and 62.73% vs. 37.27% in the LA/LA+CS group. In the ASA physical status assessment,23 11.97% of patients under GA and 10.00% of those under LA/LA+CS were classified as ASA II, and the respective percentages for ASA III were 5.13% and 6.36%. Most patients were in the other medical conditions group (asthma, epilepsy, coagulation or cardiac disorders, and celiac disease).

Table 1 Main demographic, clinical, and procedure-related characteristics of children who underwent dental surgery under general or local anesthesia with or without conscious sedation.

* Significant with p<.05. ** Significant with p<.01.

Demographics (Age: Mean age in years; Sex: Proportion of males in the group; Non-Caucasian: other non-Caucasian groups); Reason for anesthesia (Non-cooperation: reason for general anesthesia is lack of cooperation and young age; Complex surgery: reason for general anestesia is complexity of surgery; Ineffectiveness: ineffectiveness of local anesthesia: Young age: early childhood caries); Diagnosis (Deciduous tooth: persistence of deciduous teeth; dental inclusions: wisdom teeth and inclusions); Outcome of surgery (Completion: the case was completed; Successful completion: success in the procedure).

The main reason for referral to our department was minor oral surgery in both groups, general anesthesia and local anestesia with or without conscious sedation (82.05% vs. 81.82%, respectively), followed by childhood caries (8.55% vs. 3.64%) and difficulty cooperating or young age (13.68% vs. 13.64%). The most common diagnoses in GA and LA/LA+CS groups were the need for oral and maxillofacial surgery (34.19% vs. 36.36%) and caries (18.80% vs. 43.64%) (Table 1).

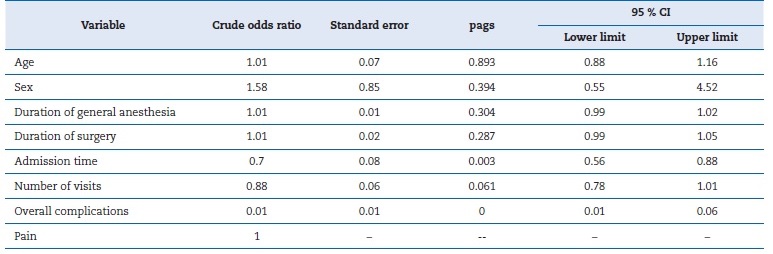

No significant between-group differences were observed for the type of treatment required. Simple exodontia procedures were more common under LA/LA+CS than GA (38.18% vs. 12.82%), as well as permanent tooth extractions (38.18% vs. 12.82%). The rates for primary tooth extractions were similar between groups (17.27% for LA/LA+CS vs. 21.37% for GA). Deep sedation lasted 41.01±1.96 minutes for GA and 27.25±2.02 minutes for LA/LA+CS. Procedural success rates were similar, although slightly higher for GA than LA/LA+CS (94.87%, 95% CI: 0.90-0.99 vs. 91.82%, 95% CI: 0.87-0.96). Overall, major complications were more common for procedures performed under GA (4.27% vs. 3.64%). The main complication in the GA group was intense pain, reported in 2.56% of interventions (Table 1). The only significant variable in the univariate analysis was overall complications (which included milder forms of pain) (Table 2).

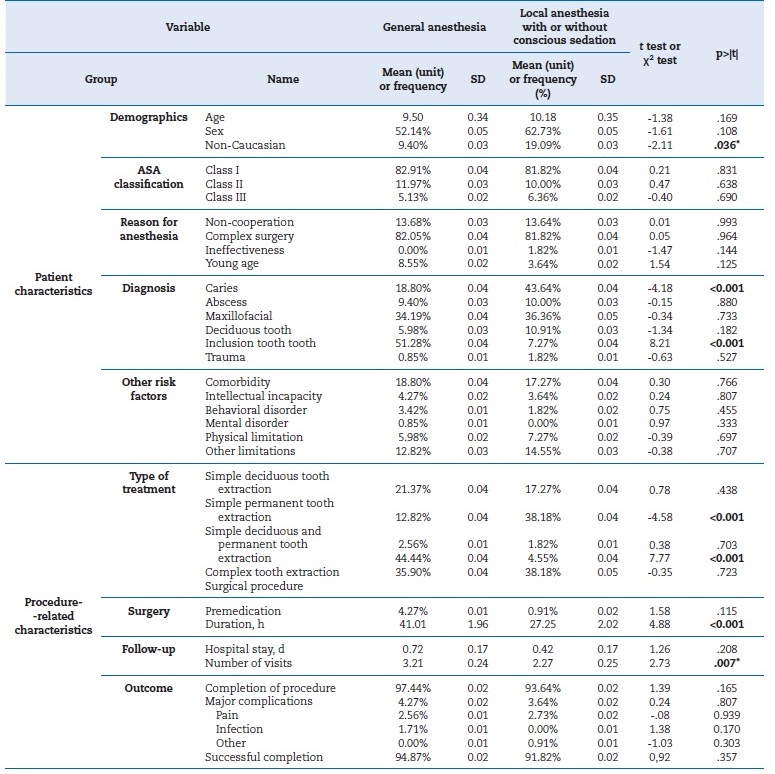

Table 2 Primary outcome variable (procedural success) versus main study variables (univariate analysis).

Crude odds ratio: unadjusted odds ratio; pags:; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. The main outcome variable is success (successful surgery).

In the logistic regression model, no significant effects were observed for GA compared with LA/LA+CS on procedural success, with an odds ratio of 1.65 (95% CI: 0.57-4.79). None of the variables (reason for treatment, diagnosis, age, or sex) had a significant effect when added, and we therefore retained the adjustment for age and sex (Table 3).

Discussion

Minor oral surgical procedures are both effective and safe when performed under GA or LA/LA+CS. Post-operative complications are also uncommon in this setting.

Restorative and surgical treatments are more common in pediatric patients with special needs, while restorative treatments are more common in pediatric patients in general due to the high incidence of early childhood caries.3,6 The situation is different in our department, where treatment decisions are dictated more often by procedure complexity (oral or maxillofacial surgery) and, to a lesser extent, the presence of caries (18.80%). Just 13.68% of patients in the GA group had difficulties cooperating. In addition, the proportion of patients in each category was similar between the GA and LA/LA+CS groups. Simple extraction of permanent teeth was performed more often under LA/LA+CS than GA (38.18% vs. 12.82%). GA, by contrast, was more common in complex extractions, such as removing dental inclusions or supernumeraries (51.28% of cases vs. 7.27% for LA/LA+CS).

Based on our review of the literature, the most common medical conditions in pediatric dental patients with special needs are complex disabilities,17 intellectual disabilities of any degree (74%),24 autism spectrum disorders (24%), cerebral palsy (16%), Down syndrome (9%),25 general developmental disorders such as autism (12%), genetic disorders and chromosomal abnormalities such as Down syndrome (13%), neurological disorders (13%), cardiac abnormalities (14%), and developmental delay (14%).8,26 Some children had more than one diagnosis, which, in some cases, could reflect manifestations of some of the syndromes mentioned above. In a study of special needs patients receiving dental treatment under GA, Mallineni and Yiu27 reported that 60% had central nervous system disorders, 30% had a syndromic disorder, and 12% had cardiovascular disease. Patients may also have visual, auditory, or language disorders.8 Finally, many children have syndromes and multiple diagnoses, such as epilepsy, sensory impairment, and behavioral disorders.8,17,26-28

In this study, patients with special healthcare needs were divided into six groups: intellectual disability, behavioral disorders, mental disorders, physical limitations, psychological limitations, and other medical conditions. Combined, these patients accounted for 18.80% of patients who received GA, which is similar to the rate of 22% reported by Akpinar.8 Other studies reported rates ranging from 50% to 67% of special healthcare needs patients requiring GA.24,29 We observed no significant differences between types of treatment or comorbidities in patients with special needs. In our department, similar to the rate of 83.9% reported by Bryan.29 The 6% of patients in whom LA/LA+CS was unsuccessful completed treatment under GA. The considerable differences observed in the success rate between our study and that of Blumer et al. may be due to differences in the definition of success: while Blumer et al. compared the longevity of restorations, we compared procedures completed without major complications.

Dental restoration materials are often chosen based on the extent of the caries, with less consideration given to how long they will last. Thus, there is potential for bias when outcomes are measured by longevity, as higher success rates might be observed for metal crowns compared to amalgam restorations.

The main complication in our study was intense pain, reported for 2.56% of procedures performed under GA. Farsi et al.30 reported a similar rate of 4%, while Akpinar8 reported the need for narcotic analgesics in 3% of patients. In the study by Erkmen et al.,9 27.10% of patients reported pain 24 hours after the intervention.

Our study has some limitations, including those inherent to the study population, since pediatric patients, especially those with special healthcare needs, constitute a heterogeneous group with numerous comorbidities that can distort comparisons. We attempted to address this potential source of bias by excluding patients with complex syndromes. In addition, due to variations in care processes, patients initially scheduled for LA/LA+CS might actually be treated with GA.

This variability was minimized in our study due to being conducted in a small department with few surgeons, and the initial indication was maintained in practically all cases. Another limitation of our study, like most of the series published to date, is the small sample size. We hope to perform a meta-analysis in the medium term to provide a more robust estimate of the differences between GA and LA/LA+CS in pediatric dental patients. We also plan to conduct a cost study based on our findings in this study.

Conclusions

Compared to LA/LA+CS, GA is not associated with a higher procedural success rate or a higher risk of complications other than mild pain in pediatric dentistry patients. Neither anesthetic technique has shown differences in complications in minor oral surgery procedures. The indication for GA use must follow specific criteria regarding procedure selection, the patient’s medical conditions, and their ability to collaborate.