Introduction

A calcifying odontogenic cyst (COC) or Gorlin cyst is an unusual lesion derived from the odontogenic epithelium.1‑3 Despite being described by Gorlin4 as a cystic lesion, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified this lesion in the odontogenic tumor section, renaming it as calcifying odontogenic cystic tumor (COCT), in 2005.5 This change was justified by the fact that COCs exhibit two variants - one cystic and one solid, with distinct clinical, radiographic, microscopic, and biological behaviors.1‑3,5

In 2017, after much discussion about COC’s origins, the WHO reincluded it in the odontogenic cyst category. On the other hand, solid neoplasms are still classified as tumor lesions under the same previously established nomenclature of dentinogenic ghost cell tumor (DGCT).6‑7 Clinically, COCs have no sex or jaw preference aand often occur in the canine region and anterior to the first molars.2‑3,8 Histopathologically, COCs present as a pathological cavity lined with ameloblastomatous epithelium with ghost cells and a variable amount of calcified material.9

The maxillary location may be common not only to odontogenic lesions such as COCs but also to maxillary sinus lesions, like antral pseudocysts (APs) or non‑secretory cysts. APs are characterized by an increased sessile volume on the maxillary sinus floor formed by the accumulation of a serous inflammatory exudate with the lining epithelium from the maxillary sinus epithelium - hence the name pseudocyst.10‑13 This histopathological aspect distinguishes this lesion from other maxillary sinus cysts, such as retention cysts or secretor cysts.10‑12

Reports of COCs associated with other odontogenic lesions, such as odontomas, ameloblastomas, ameloblastic fibromas, ameloblastic fibro‑odontomas, calcifying epithelial odontogenic tumors, and odontoameloblastomas, are available in the literature.14 On the other hand, no publications associating COCs with non‑odontogenic lesions have been published to date. In this context, this study aims to report a previously undescribed association between a COC and an AP, describing histopathological findings and treatment management for both lesions to avoid complications such as buccal‑ sinus communication.

Case report

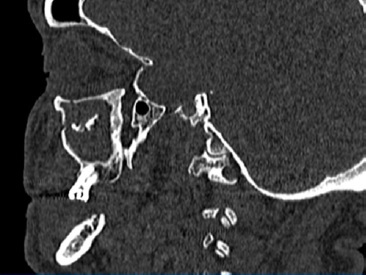

A 66‑year‑old male patient presented at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery with a lesion on his right maxillary alveolar ridge with 6 months of evolution and no symptoms (Figures 1 and 2). Radiographic examination revealed a well‑circumscribed radiolucent lesion between dental elements 13 and 15 and a second radiolucent lesion, with inaccurate limits and a central radiopaque area, in the maxillary sinus. A computerized tomography scan displayed an extensive hypodense lesion that caused veiling of the maxillary sinus at axial cuts (Figure 3) and sagittal cuts (Figure 4). Given these findings, the diagnostic hypotheses were a periapical cyst for the first lesion and a COC for the second lesion. Therefore, an incisional biopsy surgical procedure was performed under local anesthesia for diagnostic purposes. The histopathological diagnosis was a COC associated with an AP.

Figure 4 Hypodense lesion causing maxillary sinus veiling in the sagittal section of the computerized tomography.

A surgical procedure was performed under local anestesia with 3% mepivacaine and epinephrine 1:100000. Initially, surgical access was made on the crest of the maxillary boné ridge and an anterior relaxing incision in the region of the superior lateral incisor. Then, the mucoperiosteal displacement of the entire anterior region of the maxillary sinus was performed, and a bone window was made for complete access to the lesion within the maxillary sinus. After exposing the lesion, complete curettage and cystic enucleation were perr formed, and the entire lesion was sent for further anatomopathological

analysis (Figures 5 and 6). In addition, the canine dental element was extracted. Finally, the suture was made with a 3‑0 silk suture thread.

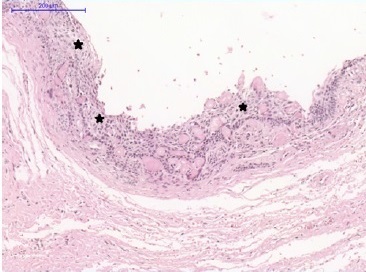

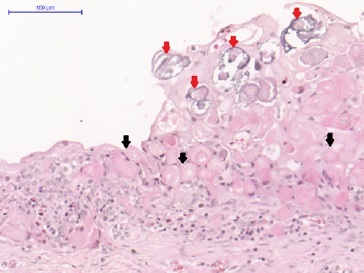

Light microscopy analysis of the first lesion revealed a cystic lesion of odontogenic origin characterized by a pathological cavity lined with both a stratified and a simple paved epithelium, presenting cells from the columnar basal layer, similar to ameloblasts. In some areas, the overlying epithelium layers were loosely arranged, resembling the stellate reticulum of the enamel organ. In addition, numerous ghost cells were observed within the epithelial component as fused cell masses, forming large sheets of amorphous and acellular material in the fibrous connective tissue capsule. These findings confirmed the COC diagnosis (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7 Calcifying odontogenic cyst. Pathological cavity lined with ameloblastomatous basal layer epithelium (stars). Overlying layer cells are loosely organized, resembling the stellate reticulum.

Figure 8 Calcifying odontogenic cyst. Numerous ghost cells within the epithelial component (black arrows), organized as fused cell masses forming large sheets of amorphous and acellular material in the fibrous connective tissue capsule and calcifications (red arrows).

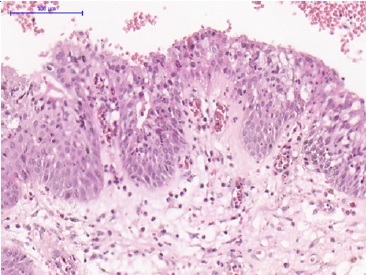

The histopathology analysis of the associated lesion demonstrated a loosely arranged, swollen connective tissue fragment with intense mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate areas permeating large amounts of slightly eosinophilic amorphous material. In addition, the maxillary sinus had two types of epithelia: a ciliated cylindrical pseudostratified epithelium and a non‑keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, partially involving the lesion. Due to these findings, the histopathological diagnosis was an AP (Figures 9 and 10). Subsequently, enucleation with lesion curettage was performed. The patient has been followed up for 5 years and has no signs of clinical recurrence (Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 9 Antral pseudocyst. Multiple epithelium‑lined cystic compartments and loose connective tissue (blue stars) presenting mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates (green stars) and extravasation of mucin‑compatible eosinophilic material (yellow stars).

Figure 10 Antral pseudocyst. Details of the non‑keratinized stratified squamous epithelium of the antral pseudocyst. (Hematoxylin‑eosin; scale barr: 200μm in A, 100μm in B, 500μm in C, and 100μm in D).

Discussion and conclusions

Several studies have proven the rarity of COC lesions, estimated as corresponding to 1% to 3% of all odontogenic cysts and tumors.15,16 In addition, the peak occurrence of this type of lesion is between the second and third decades of life.8,17 Thus, since the patient in this case report was 66 years old at the time of diagnosis, he may have been diagnosed late, which would explain the greater bone growth and expansion observed. COCs may be intraosseous or peripheral, the latter being extremely rare.1,17 Radiographic findings include multilocular or unilocular radiolucent lesions that may contain irregular foci of calcifications.1‑3,18 Teeth displacement and root resorption are relatively common.19,20 Regarding biological behavior, COCs present an indolent course, contrary to the DGCT, which explains their distinction by the WHO in 2017.1‑2,6,8,21 In the present case, the lesion presented a unilocular aspect with a thin radiopaque halo and no root resorption or displacement of the associated dental elements 13 and 15, despite bulging of the cortical bone. The association with dental apices and the indolent clinical‑radiographic behavior of the COC led to the clinical hypothesis of a radicular cyst.

The literature recommends enucleation associated with lesion curettage, although marsupialization/decompression is also among the treatments of choice for larger lesions to reduce cyst size and surgery length. This maneuver has improved prognosis, leading to low recurrence rates (approximately 5%).22

In this report, due to the lesion’s size and well‑circumscription, enucleation associated with curettage was performed. The success of this conservative treatment is evidenced by the lack of recurrences in the last 3 years of follow‑up. COCs may be associated with other odontogenic lesions, and the literature commonly reports association with odontomas and ameloblastomas. Dentigerous cysts are considered the most frequent cysts. In addition, impacted or dislocated adjacent teeth are also frequent.23 In another study, three COCs were associated with odontomas and one with ameloblastomas.24 The present case report suggests an association between a COC and an AP, which has not been mentioned in the literature. APs are solitary, dome‑shaped radiopaque masses located on the maxillary sinus floor that can further reduce the size of this anatomical structure.11‑13,25,26,27 This finding is consistent with the present case since a veiling of the maxillary sinus caused by the AP was observed, and the central radiopaque area in the maxillary sinus led us to hypothesize a diagnosis of COC for the lesion in the antrum (rather than the periapical one).

APs are often detected on routine radiographic examinations. Surgical excision in these cases is unnecessary, as studies have shown no progression or even regression during follow‑up.11,12,25 When present, symptoms range from headaches to face pain and nasal obstruction and discharge.12,25 In some cases, a positive aspiration mimicking a cystic lesion may be present.13 Given these clinical and radiographic findings, the literature indicates mucocele of the sinus and odontogenic cysts as differential diagnoses.11,13 Due to the mixed radiographic aspect of the AP in the maxillary sinus region, the clinical hypothesis of COC was raised. The literature reports that COCs can present at this location and even mimic a sinus mucocele.3,28

Although APs’ etiology is not well understood, other studies report allergies, barotrauma, rhinitis, rhinosinusitis,12,25 periapical infections,10,11,25 periodontitis,10,25 viral infections of the respiratory tract, and mucosal irritations caused by lack of air humidity13 as possible factors. Since COCs are a noninflammatory odontogenic lesion, they are unlikely to cause APs’ development. The radiographic appearance observed in the present case, which indicates a clear separation between the two lesions, may support this hypothesis. Further medical investigation is required to confirm if the patient has a history of allergies or respiratory tract infections.

Beaumont et al.,29 recommend a Caldwell‑Luc surgery or sinus endoscopic surgery as the ideal treatment in cases of sinus graft when APs are present and advocate the complete removal of the sinus lining to prevent a recurrence. These authors also suggested at least 6 months of healing after lesion removal before performing sinus enlargement. According to Yu et al.,30 the period of 6 to 12 months for sinus enlargement after AP removal allows for the regeneration of a new ciliary respiratory epithelium. However, high rates of complications and operative trauma can create challenges in terms of patient cooperation. Before raising the sinus floor, mucus aspiration is performed to reduce the cyst size and decompress the pressure. In the present study, AP enucleation was performed due to the small size of the lesion, without maxillary sinus floor elevation, since this structure was not compromised.

Antroliths are known to be rare. Their nidus can be exogenous or endogenous.31 Given the anatomic structure of the maxillary sinus, namely the small ostium diameter hidden in the middle meatus, foreign bodies from the nasal cavity or nostril are expected not to enter the antrum. On the other hand, endogenous materials may include tooth, bone fragments, blood, pus, and, more interestingly, fungus ball (e.g., aspergilloma or mycetoma), so APs may arise from previous inflammation.32

This case is the first report of an association between a COC and an AP in the maxilla. The main explanation for this finding is that the COC’s growth, associated with an inflammatory process, would stimulate the sinus epithelium to form the AP in the maxillary sinus, given the inflammatory etiology associated with most AP cases and the possible inflammatory infiltrate found in COC.